Neuroanthropology.net is pleased to bring you the 71st edition of Four Stone Hearth, the itinerant swagman of the anthropology world, with blog entries herded together from all corners of this immense anthropological territory. A Hot Cup of Joe will be hosting the next edition in two weeks time, so, if you couldn’t get your listing into this edition, and don’t want to just stick it in the comments, get in touch with Joe.

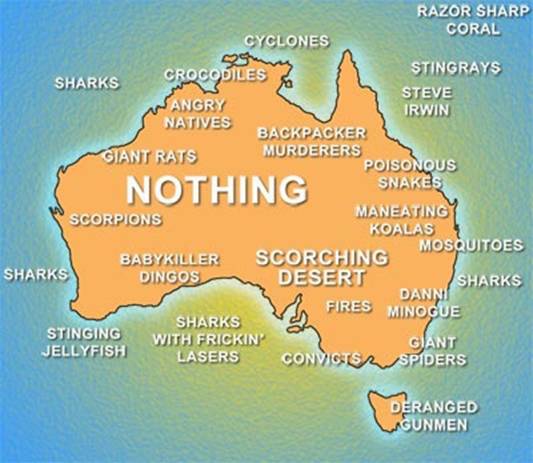

Because I need to study for my citizenship test for my adopted home, Australia, I thought I would lace some crucial Australiana into this particular carnival. Apologies, but that’s the best theme I’ve got, so if you want to skip the extraneous info about Oz, just ignore the text in the block quote boxes and stick to the main trail.

Really old humans

At Anthropology.net, editor Tim Jones offers an extended discussion of the use in archaeology of ‘optimal foraging’ theory to understand the range and foraging catchment of a Spanish community around 10-14,000 BP. Jones especially likes the detailed discussion of the contemporary geography and flora, as well as the way that an analysis of the costs and benefits of butchering was included in the estimates of foraging area. The original article by Marín Arroyo is also available if you want to check out both the published version and the online discussion.

John Hawks is on the trail of a bone, possibly a biped femur, that can be seen in a photo of the Toumaï skull, Sahelanthropus remains. Hawks flagged that there would be more discussion of this femur in May, but points out the difficultly involved in judging whether the femur is evidence of bipedalism or its absence.

Geoff Manaugh at the BLDGBLOG offers ‘Origin and Detour,’ a musing on the political and even emotional implications of new ‘into Africa’ theories that human originated, not in iconic African locales like Olduvai, but rather in Europe and then later migrated to Africa. The post is inspired by a story in New Scientist.

The dingo was likely brought to Australia by human immigrants from Southeast or South Asia, as late as 4000 years ago; no dingo remains are found in Tasmania, which was last connected to mainland Australia 12,000 years ago. The dingo likely caused the extinction of what were later referred to as the Tasmanian Tiger and the Tasmanian Devil from mainland Australia. The longest fence in the world stretches across the states of Queensland and South Australia to try to keep dingoes away from sheep herds: 5531 kilometres.

Brains and culture

Babel’s Dawn author, Edmund Blair Bolles, discusses a recent article on speech evolution Francisco Aboitiz and Ricardo Garcia, published in Reviews in the Neurosciences. The article shifts the focus away from isolating the single trait that distinguishes human speech from other species’ capacities and proposes a network rather than isolated brain area as responsible for the fundamental incommensurably of language with other biological phenomena. The article, and Bolles’ reflection, focuses especially the arcurate fasciculus which links Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas and has been offered as a possible neural area responsible for working memory.

Edmund also covers how over-heated coverage of some recent research becomes: monkeys have grammar!

Nicolas Baumard at Cognition and Culture discusses the Visual Word Form Area in the brain and writing, arguing that the ‘neuronal recycling hypothesis’ of Dehaene and Cohen suggests that cultural forms make use of evolutionary older brain circuits and inherit their constraints, shaping how something like writing system can work.

Although not strictly anthropology, Neuroanthropology loves the blog Mind Hacks. Vaughan covers some of the best neuroscience research, often with fascinating implications for the study of human diversity, evolution and other anthropological issues. Two recent pieces on the genetic correlates of schizophrenia, one on popular misunderstandings of ‘heritability’ and another on the possible role of copy number variations, are great examples of why Vaughan is one neuropsychologist who doesn’t leave us pulling out our own hair.

There are an estimated 40 million kangaroos in Australia (more than people). Unlike other ruminants, like cattle, kangaroos emit no methane, converting the hydrogen by-product of fermentation into acetate, which they can then use as food. Some scientists are trying to transfer the bacteria responsible for this conversion to cows to cut down on their greenhouse gas emissions.

Scientific and not-so-scientific worldviews

Razib Khan at Gene Expression runs some comparisons on attitudes toward and awareness of evolutionary theory and religious faith, drawing on a recent Zogby survey commissioned by the Discovery Institute (discussed by John Lynch on his blog, A Simple Prop) and the 2005 World Values Survey. Khan discusses the contradicting attitudes toward evolution in different countries, offering some historical-political explanations for diverging relations between religiosity and acceptance of evolution.

A scientific revolution happened in medicine in the 16th Century alongside the Enlightenment revolution in physics and astronomy, with Galen’s classical anatomy under attack from a number of experimental physicians. Eric Michael Johnson of the Primate Diaries argues that the intellectual independence and spirit of experimentation was more a quality of craftsmen then of the hidebound, conservative scholastic classes.

The deep and sinister link between Charles Darwin and Adolf Hitler is exposed by Eric Michael Johnson at Primate Diaries. Okay, actually it’s the opposite, as yet another crank strategy to try to discredit Mr. Darwin turns out to be full of, well, missing links, as the case for Darwin’s hidden eugenic agenda can’t stand up, on two or four feet.

Similarly Afarensis takes a close look at the Texas Social Studies Standards and discovers that they are flakier than those for science. Some of the board members seem to have real problems with activists and other uppity people being considered historically important.

Charles Darwin visited Australia near the end of the Beagle’s voyage. He spent about two months visiting in 1836, and although he was initially enthused about Sydney, found marsupials fascinating, and thought highly of the Aboriginal people, whom he noticed were being depleted, his mood soured.

‘On the whole I do not like New South Wales. It is no doubt an admirable place to accumulate pounds and shillings; but heaven forbid that I should live where every man is sure be somewhere between a petty rogue and a bloodthirsty villain.’

(Darwin to Henslow)

Walking and camping in ruins

On strolls through the ruins of Umm al-Jimal, Umm Cais and other sites in Jordan, Colleen Morgan of Middle Savagery sees the traces of so much excavating yet to be done. Her archaeological travelogue fills in some of the details that we don’t often see in excavation reports: the surrounding towns, the well-meaning but ill-conceived attempts at reconstruction, the jumble of spaces between and traces of what lies outside the areas that get carefully excavated. Also check out the earlier post for her trip.

Magnus Reuterdahl returns to the elk hunting camp where he spent days in his youth with his father, realizing that what he was told were ruins of a fallen church are more likely cairns. Although not as romantic as tales of churches abandoned during the plague and platforms for ancient trials, Magnus helps explain where Testimony of the Space originates.

Although Australia has a reputation for being settled by convicts, from 1788 to 1856, 157,000 convicts were sent to Australia. This is only one-third of the total sent to the United States.

They’re watching us (and taking pictures)

Don’t look now, but you’re been watched. At Old Dirt, New Thoughts, Brian shares images from Google Earth of his camp at Aniakchak Bay in Alaska.

And it’s been happening for a while, as Martin Rundkvist of Aardvarchaeology shows, with a release of 1950s Aerial Pictures of the Swedish Countryside that are now available on the internet.

Although Australia is 50% larger than Europe, it has only approximately 22 million people, making it the lowest population density of any country in the world (less than 3 people/sq. km on average). More than 85% of Australians live within 50 kilometers of the coast, which stretches for 50,000 km and has more than 10,000 beaches. The largest cattle station in Australia, the Anna Creek Station, covers 34,000 sq kms. (6 million acres). Because that area is so mind-bendingly huge, I must now compare it to some other equally unimagineable geographical entity: it’s about the size of Belgium!

Objects and artifacts: material culture from baskets to bare feet

Tim at Remote Central provides a massive discussion of basketry and weaving, moving from some video and discussion of the integration of decorative kachina motifs into basketry among the Hopi to speculation based on circumstantial evidence about how old weaving techniques might be in human history.

On the blog Material Culture, Haidy posts a discussion of a remarkably civil disagreement between scholars on how to approach material culture, pitting Daniel Miller against Martin Holbraad, advocate of ‘ontography.’ Miller adds a thoughtful response, but you can also follow some of the thinking to an earlier entry from May on Savage Minds by Olumide Abimbola.

Alex at Golublog gives us notes and photos from Kenmaity Chicken in a discussion of the difference between tourists’ and ethnographers’ vision, but also about the slippery boundaries around an ethnographer and the missing details when just living in a fieldsite, and doing things like eating chicken with friends under posters of small children with flying chicken parts.

Recent research on running by our hominid ancestors and high incidence of injury among contemporary runners has led to a series of articles on the benefits of running barefoot. Zinjanthropus throws a bit of cold water on this particular brand of ‘paleo-nostalgia.’ (I’ve got a longer post on the ‘throw out your shoes’ movement on the way, so check back in a couple of days.)

Looting Matters carries an update on objects stolen from Iraqi museums that have wound up at auctions and ongoing efforts to track, identify and return these artifacts. David Gill includes a number of important links on the subject.

Ryan Anderson at Ethnografix pays back a bit of his own ‘intellectual debt,’ especially for his early interest in photography, to the documentary photographer Dorthea Lange. It’s only a brief post, but it links on to some moving images.

Mathilda’s back and she’s noticing mustaches on Egyptian statues. The video is here.

In a short post that ranges far, Centauri Dreams author Paul Gilster discusses new efforts to increase the longevity of digital storage, a key technology not only for long-range space flight but also for a ‘planetary backup plan’ in case either external disaster or internal conflict cause humanity to slip into another Dark Age. As Gilster points out, many of the new information storage technologies we now rely upon are not nearly as durable as vellum, nor can we be certain that future archaeologists will know how to access materials that we store electronically, even if water, magnetism or other degrading agent doesn’t intervene in the meantime.

Vegemite, a paste made of yeast extract and made famous outside Australia by Men at Work’s song, ‘Down Under,’ is possibly one of the most vile edible substances on the planet (alright, maybe that’s not a ‘fact’). Kraft is introducing a new recipe for a second version of Vegemite this month (the original was created in 1923 – I’ll keep you posted how this ‘new recipe’ thing goes… it’s supposedly more ‘buttery’). The yeast extract is a by-product of beer manufacturing, so, technically, yes, Australian school children are routinely fed beer by-products from an early age.

Social relations, others and animals

Never one to refuse the horns of the bull, Max Forte at Open Anthropology, continues to dig into the moral and political grounding of the Human Terrain Systems project.

Greg Laden compares mail order Korean and Russian brides (the latter apparently getting some ad space on Scienceblogs.com) to the situation of foragers and villagers in some parts of the Congo, where foraging woman have the option of engaging in ‘hypergyny,’ or ‘marrying up’ (in terms of money, status, power, and other resources). What’s especially interesting is that Greg links the phenomenon to what he calls ‘gene stealing,’ where invading groups can actually gain environmentally crucial genetic immunities and other advantages out of the relationship.

Keith Hart at The Memory Bank posts a copy of a speech that he gave at the launch of the book, Working in Warwick: including street traders in urban plans. From the perspective of his long relationship to Durban, South Africa, he discusses how the informal economy works in the struggle between democracy and inequality.

Adam Henne points to a fascinating article about whales watching humans in The New York Times and discusses some of the implications for the moral lives of animals in human worlds.

Voting is compulsory in Australia, leading routinely to 95% voting rates in elections (failing to vote brings a fine if you do not have a valid reason for missing the election). Women gained the right to vote in South Australia in 1894; only New Zealand introduced women’s voting rights earlier in in the modern era. In 1901, all women (except Aboriginal Australians) gained the right to vote in the country.

Aboriginal Australians actually voted in the first Commonwealth Parliament election in 1901 at some out-stations, but a later legal ruling stripped them of their right. Federal voting rights were not truly restored until 1962, but they could not be compelled to vote like other Australians if they did not choose to enrol.

Book reviews and discussions

Tessa Valo writes a very thorough review of Assa Doran’s book on boatmen on the Ganges at anthropologi.info, bringing up a fair set of critiques, but also describing in detail the account of relations of these workers to higher caste individuals and to the state.

John Postill offers a discussion of Tom Boellstorff’s Coming of Age in Second Life in his own blog.

The only domesticated food plant that has been cultivated on an industrial scale to originate in Australia is the macadamia nut.

Announcements, media, links and other news

You Northern Hemisphere types are no doubt enjoying some time off, but that doesn’t mean everything’s stopped happening.

Mark Dingemanse announces the launch of the web page for the Language & Cognition group’s project, Synaesthesia across cultures. The group is looking for additional collaborators to ‘gather cross-cultural data on the forms and prevalence of synaesthesia.’ The pilot uses low-tech methods that are easy to replicate in the field.

Although she’s on vacation, Pamthropologist of Teaching Anthropology felt compelled by a video put together by students in cultural anthropology at Sussex County Community College to pull out the keyboard and post up the vid. It’s a Michael Wesch (of Kansas State ethnographic video) style presentation of their own ethnographic research on other students like themselves.

Here at Neuroanthropology, Daniel’s posted two recent items on a pair of our favourite anthropologists, one on Tim Ingold and another a video clip on Paul Farmer.

If you’re interested in podcasts, see also the review of a series of lectures from Oxford at Anthropology.net.

Somatosphere’s taking some time off for summer travels, so Eugene put up the top ten most popular postings from that site from their first year of being online. Remember, if you haven’t read it, it’s new to you.

The cane toad (Bufo marinus), native to the Americas, was introduced to Australia in 1935 to help stem cane beetles. This poisonous amphibian has since become an invasive pest, spreading as far as Western Australia. The toad is so prevalent that it is putting selective pressure on snakes in the areas it lives, causing small-headed variants, with mouths too small to attempt eating the poisonous animals, to become more prevalent.

Tooooo much time on-line makes you laugh at everything…

Lisa Wynn at Culture Matters has a short but fun post on a proposal by Princeton University faculty to ‘Lockheed Martin to identify irony and weaponize it.’

If you haven’t been playing along, you can catch the rolling game ‘When on Google Earth.’ If you can identify the archaeological site and the period of construction first, you get to set the next satellite-view challenge. Last entry as of this writing was WOGE 67 at Iconoclasm, which also includes the table of previous winners and locations.

And it turns out that other apes laugh too.

There’s even video at Discovery News.

Thanks especially to Tim Jones at Anthropology.net and, of course, my collaborator Daniel Lende, for helping put these references together. Of course they bear no responsibility for the Australiana. And if we missed you, it’s not out of malice. Please drop us a line and we’ll make sure there’s a link to what you’ve been posting.