![]() Making the rounds of neuro-related sites on the web is a recent story from Wired, Brain Scanners Can See Your Decisions Before You Make Them, by Brandon Keim. It’s an interesting short piece on an even more interesting research paper by Chun Siong Soon, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes forthcoming in Nature Neuroscience (abstract here). But like so much in the science writing about neurosciences, the piece leaves me feeling like either I don’t get it or science writers really don’t understand the significance of basic brain research. I won’t dwell too much on my issues though with the science writer because I want to really consider the relationship between brain activity and experience, or what role phenomenology might serve in neuroanthropology (besides, I’ve been railing at science writers a bit too much of late…).

Making the rounds of neuro-related sites on the web is a recent story from Wired, Brain Scanners Can See Your Decisions Before You Make Them, by Brandon Keim. It’s an interesting short piece on an even more interesting research paper by Chun Siong Soon, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes forthcoming in Nature Neuroscience (abstract here). But like so much in the science writing about neurosciences, the piece leaves me feeling like either I don’t get it or science writers really don’t understand the significance of basic brain research. I won’t dwell too much on my issues though with the science writer because I want to really consider the relationship between brain activity and experience, or what role phenomenology might serve in neuroanthropology (besides, I’ve been railing at science writers a bit too much of late…).

From Keim’s article, we have this explanation of Haynes’ work:

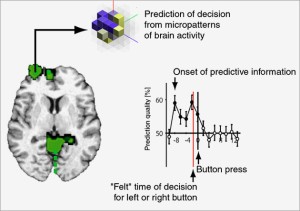

Haynes updated a classic experiment by the late Benjamin Libet, who showed that a brain region involved in coordinating motor activity fired a fraction of a second before test subjects chose to push a button. Later studies supported Libet’s theory that subconscious activity preceded and determined conscious choice [I have a problem with that phrase, especially ‘determined’] — but none found such a vast gap between a decision and the experience of making it as Haynes’ study has….

Taken together, the patterns [in frontopolar cortex and then parietal cortex] consistently predicted whether test subjects eventually pushed a button with their left or right hand — a choice that, to them, felt like the outcome of conscious deliberation. For those accustomed to thinking of themselves as having free will, the implications are far more unsettling than learning about the physiological basis of other brain functions.

The Libet research is a classic piece (I don’t know if it makes any top 100 lists, but it’s especially important to those of us interested in motor action). The problem seems to be forcing Haynes’ data — which confirms Libet’s older research about the subconscious activity that precedes conscious awareness of ‘choice’ — through a folk theory about ‘free will’ being a necessarily conscious activity setting in motion a chain of mind events leading up to action. Folk understandings posit the existence of ‘The Decider’ in the brain, a kind of uncaused cause, the prime neural mover, which is conscious.

Bottom line, as far as I’m concerned: the research can’t be proving whether or not we have ‘free will’ because ‘free will’ is fundamentally about constraints on ‘will’ (itself a fuzzy concept when you’re looking at brain imaging). That is, the research would have to examine not what the brain does when it makes a choice, but whether that brain activity was constrained by something external to the person. After all, if we say that a person’s ‘free will’ is limited by their brain, that doesn’t really make sense now, does it? Presumably, acts of a ‘free will’ would also be determined by the brain, wouldn’t they? For the brain to ‘constrain’ our own ‘free will,’ it would have to be a thing separate from us.

What the research is showing, however, is something fascinating about the relationship of phenomenology and native categories of mind and how they might intersect with brain science research.

Soon and colleagues open their article in Nature Neuroscience with the following description:

The impression that we are able to freely choose between different possible courses of action is fundamental to our mental life. However, it has been suggested that this subjective experience of freedom is no more than an illusion and that our actions are initiated by unconscious mental processes long before we become aware of our intention to act…

This is a much more subtle statement than, ‘free will is an illusion because our brains constrain our choice.’ Rather, it’s suggesting that the mental processes that eventually become action have an indirect relationship both with conscious awareness and with our own sense of what is happening in our ‘mental life.’

For me, this is about the relationship between mental experience and mental event, or phenomenology and neurology. The two are not totally separable, but they have a varied relationship depending upon what sorts of experiences/brain events we’re talking about. ‘Willing’ is a particularly interesting case to study because of Western folk and philosophical theories about how decisions take place in consciousness.

The research is only examining basic motor acts — not long-term life decisions such as whether to propose marriage or which career to pursue — but it certainly does bear on day-to-day actions. Searching for Mind also points this problem in the the debate about ‘free will,’ in the post, The core modern argument against Free Will. This experiment, for example, was just about pushing a button with the left or right index fingers, but the way ‘free will’ comes up, it sounds like a discussion of Calvinist theology of pre-destination. So one problem is that of scale; doing experiments on button pushing is likely not going to tell us much about whether major life decisions, made over months or years with complicated emotional, personal, and interpersonal deliberation, are ‘determined’ by a ‘pre-pre-motor’ neural event.

In addition, to argue that the research is undermining the notion of free will is assuming that ‘free will’ is a sequence, starting with an experiential event — the conscious decision — followed by all the observable neural events. I’m not even sure what sort of data could support this model of free will because how would we know if the neural event that comes first is ‘free’? The researchers had subjects watch letters change on a screen and then recall what letter they could see when they ‘decided’ to push one of the buttons. Because certain parts of the brain reliably became stimulated before the subjects consciously decided to press the button does not necessarily mean that these decisions are still not ‘free’? In fact, they were free, in the sense that there was no pattern to whether the subjects would push the left or right button, nor anything outside the subjects’ own brains that could predict which they would push.

While the article in Wired dwells on the ‘oh my god, we don’t have free will’ angle of interpreting this research, one of the commentators being quoted offers a much better reading of the data:

The unease people feel at the potential unreality of free will, said National Institutes of Health neuroscientist Mark Hallett, originates in a misconception of self as separate from the brain [also the source of excitement among some science writers].

“That’s the same notion as the mind being separate from the body — and I don’t think anyone really believes that,” said Hallett. “A different way of thinking about it is that your consciousness is only aware of some of the things your brain is doing.”

Hallett doubts that free will exists as a separate, independent force.

“If it is, we haven’t put our finger on it,” he said. “But we’re happy to keep looking.”

In this case, I really appreciate Hallett’s explanation, and highlights that Western folk categories of mental structures — things like ‘free will,’ ‘memory,’ ’emotion’ — are often a lousy rough description of the brain’s actual structures. In this case, ‘your consciousness is only aware of some of the things your brain is doing’ seems to me to be the crux of the phenomenology-neurology tangle.

In fact, most brain scientists would likely dispute the model that ‘free will’ is necessarily conscious on all kinds of levels. Freud, for example, would have had a huge problem with the notion of an absolutely free will, and the vast majority of social theorists — anyone that doesn’t model humans as ultimately rational actors — would also disagree. Moreover, even the most superficial accounts of motor activity make allowances for the widespread automaticity of basic actions, even popular discussions of things like ‘habit.’ So the story here for me is not so much about ‘free will’ but rather about the tenuous relationship between mental experience and event, the fact that, in many ways, we don’t know our own minds.

So do we dismiss experience entirely? No, obviously not. In fact, the experiment is interesting because the researchers compared brain imaging with subjects’ reports of experience. One is not more important than the other; the gap is what is intriguing. But I do think we need to be exceptionally wary about using the sloppiest of our native categories; ‘free will’ may be one of them, more well developed as a philosophical construct than as either an identifiable neural phenomenon or even as a rigorous phenomenologically-consistent concept. ‘Free will’ stakes out important territory, but if we go looking for ‘free will’ in the brain, we’re likely to wind up confused about what we’ve found. In this case, the research team has found that however we make decisions to push buttons, non-conscious processes might be initiating our actions rather than conscious processes, as our native model of ‘free will’ assumes.

References

Chun Siong Soon, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes. 2008. Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience Advance online publication: 13 April 2008. doi:10.1038/nn.2112 (brief communication abstract)

Thank you so much for this post. I read earlier discussion of this research on Cognitive Daily which seemed to take for granted the idea that “free will” was a valid neurological concept, and that it was challenged by this research. I felt, uneasily, that there was surely some sort of basic, invalid, assumption at the bottom of it all – and you have expressed the basis for my unease far more elegantly than I ever could.

Thanks, William, for the vote of confidence. I don’t think this research report is unusual in this sense — often, it seems to me, that very interesting empirical research is interpreted in dubious fashion using non-scientific psychological terms like ‘free will.’ I try to be understanding because I think interpreting this sort of brain imaging research is genuinely difficult; in phenomenological philosophy and other places, theorists have pointed out the difficulty of noting a link between any quality of experience and an observable phenomenon in the brain, so I hope I’m not too hard on these authors.

But I’m also glad to know that my account doesn’t seem like overly-precious semantic hair-splitting, at least to some readers.

A number of blogs have covered this, and this has been my favorite one.

Not to get into the hair-splitting game too much, but is it accurate to say that we are aware of *anything* our brains are doing? I might infer that certain things are happening, say, in my occipital cortex when I see something at a certain orientation, but this isn’t awareness of what my brain is doing.

My gut feeling is that the crux of the phenomenology/neurology divide isn’t so much a lack of phenomenal access to brain events as it is the absence of a mediating step between our phenomenological descriptions and our scientific descriptions, which tend to be based on different ontological (perhaps folk-ontological?) commitments.

I think you actually get at this in your closing remarks on this post.

I failed at my first attempt to use XHTML in a comment.

I meant to put the following passage (from your post) in quotation marks:

In this case, ‘your consciousness is only aware of some of the things your brain is doing’ seems to me to be the crux of the phenomenology-neurology tangle.

Thanks for this post.

The study has appeared on a number of blogs in a number of different contexts but always making the same point – that imaging can detect activity which suggests the decision to press a left or right button is made a number of milliseconds BEFORE we are consciously aware of having made the decision. The accuracy of the prediction based on imaging has been reported at approximately 60% if I recall correctly.

Whilst this accuracy is greater than chance, meaning the prediction has some validity, I think that the conclusion that humans only have an illusion of free will is a very poor one. The decision to press a left or right button is essentially a “random” decision, as random as choosing A or B can ever be from within your own mind, rather than flipping a coin. My point is that, in a “random” decision such as this, is it really surprising that micropatterns in neural activity, which could easily be described as neural “noise” give the person a subconcious inclination to chose one button over another? As the person may feel they are choosing the button “at random” using their own “free will” this is not surprising at all.

Now, if we consider a “reasoned” as opposed to “random” use of free will, the pattern might be very different. Consider quitting smoking cigarettes, which is a hard act of free will, requiring “willpower”. In this case, although it is not yet possible to detect this, we could hypothesize that there would be micropatterns in neural activity relating to dopamine activation of synapses following nicotine inhalation, that give the person a subconcious craving to continue smoking. If an MRI scanner could detect this activity, we might be able to predict if a person would find it easier or harder to quit smoking, with say, 60% accuracy.

Whilst it is arguable that a person might not be able to quit cigarettes if the addiction and craving exceeds their “willpower” it is ridiculous to argue that the person in the study above would not have been able to change their mind and press a different button, should they so wish. This ability, to inhibit our actions and responses, is tested by neuropsychological tests such as the Stroop Test. I would argue that the ability to inhibit our actions and/or change our minds, examples of Executive Function, are an example of a limited capacity for “Free Will” or “Willpower”. The fact that we might chose button A randomly over button B and that this random decision is influenced by neural noise of which we are not conscious does nothing to disprove the concept of Free Will.

A person doesn’t realize that his inner system of desires has already made all the calculations and put out the result. Such studies prove what Kabbalah has been saying all along: everything depends on our desire, and not on our external, philosophical reasoning. Thus, only the Upper Light can correct us; we cannot correct ourselves on our own