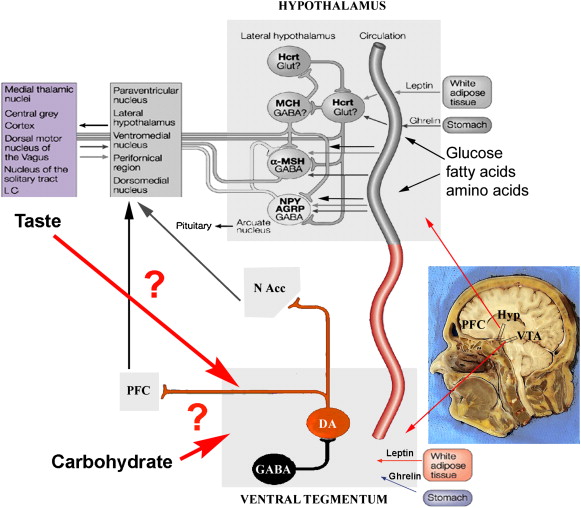

In an earlier post The Sugar Made Me Do It, I covered recent research by de Araujo, Oliveira-Maia et al. on how food, specifically sucrose, can reinforce eating by activating mid-brain dopamine circuitry, even in the absence of taste. In the accompanying editorial essay by Andrews and Horvath, this great graphic appeared, representing what is known about how eating can act on the hypothalamus and on the mesolimbic dopamine system (ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, and prefrontal cortex).

Here is a much more convincing link to how eating can become appetite-driven, which previous posts on Genetics and Obesity and On the Causes of Obesity had raised as an important issue in the obesity problem.

Just one more note on the graphic: in terms of how taste can affect dopamine function, see some thoughts in the post on the neuropeptide orexin.

Figure 1. Schematic Illustration Depicting Some of the Major Findings of de Araujo and Oliveira-Maia et al

Taste alone (noncaloric sweetener), taste with caloric value (sucrose solution), or caloric value only (in the absence of taste receptors) can all equally activate the midbrain reward circuitry. To date, major emphasis has been placed on the hypothalamus and its various circuits, including orexin (ORX/Hcrt)- and melanin concentrating hormone (MCH)-producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus as well as neuropeptide Y (NPY)/agouti-related protein (AgRP)- and -melanocyte-stimulating hormone (-MSH)-producing neurons in the arcuate nucleus, as a homeostatic center for feeding, responding to various peripheral metabolic hormones and fuels. The mesencephalic dopamine system is also targeted by peripheral hormones that affect and alter behavioral (and potentially endocrine) components of energy homeostasis. The results by de Araujo and Oliveira-Maia et al. highlight, however, that without classical hedonic signaling associated with reward-seeking behavior, the midbrain dopamine system can be entrained by caloric value arising from the periphery. While the precise signaling modality that mediates caloric value on dopamine neuronal activity remains to be deciphered, overall it is reasonable to suggest that distinction between hedonic and homeostatic regulation of feeding is redundant. DA, dopamine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; Glut, glutamate.