The most recent edition of Behavioral and Brain Sciences carries a remarkable review article by Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan, ‘The weirdest people in the world?’ The article outlines two central propositions; first, that most behavioural science theory is built upon research that examines intensely a narrow sample of human variation (disproportionately US university undergraduates who are, as the authors write, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, or ‘WEIRD’).

The most recent edition of Behavioral and Brain Sciences carries a remarkable review article by Joseph Henrich, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan, ‘The weirdest people in the world?’ The article outlines two central propositions; first, that most behavioural science theory is built upon research that examines intensely a narrow sample of human variation (disproportionately US university undergraduates who are, as the authors write, Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic, or ‘WEIRD’).

More controversially, the authors go on to argue that, where there is robust cross-cultural research, WEIRD subjects tend to be outliers on a range of measurable traits that do vary, including visual perception, sense of fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, and a host of other basic psychological traits. They don’t ignore universals – discussing them in several places – but they do highlight human variation and its implications for psychological theory.

As is the custom at BBS, the target article is accompanied by a large number of responses from scholars around the world, and then a synthetic reflection from the original target article authors to the many responses (in this case, 28). The total of the discussion weighs in at a hefty 75 pages, so it will take most readers (like me) a couple of days to digest the whole thing.

It’s my second time encountering the article as I read a pre-print version and contemplated proposing a response, but, sadly, there was just too much I wanted to say, and not enough time in the calendar (conference organizing and the like dominating my life) for me to be able to pull it together. I regret not writing a rejoinder, but I can do so here with no limit on my space and the added advantage of seeing how other scholars responded to the article.

My one word review of the collection of target article and responses: AMEN!

Or maybe that should be, AAAAAAAMEEEEEN! {Sung by angelic voices.}

There’s a short version of the argument in Nature as well, but the longer version is well worth the read.

Of course, I have tons of quibbles with wording or sub-arguments, ways of making points, choices of emblematic cases and the like in the longer BBS article (and I’ll get to a couple of those below the ‘fold’), but I don’t want to lose my over-arching sense that there is so much right in this piece. So before I get into the discussion, I just want to thank all of the authors, not just Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan, but also the authors of the responses, who pulled it together when I didn’t try. The collection is a really remarkable discussion, one that I find gratifying in such a prominent place, and I do hope that the target article has a significant impact on the behavioural sciences.

If you have one blockhead colleague who simply does not get that surveying his or her students in ‘Introduction to Psychology’ fails to provide instant access to ‘human nature,’ this is the article to pass along. If that colleague still doesn’t get it, please stop talking to them. Really. You. Are. Wasting. Your. Breath. If Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan don’t shake their confidence, I’m not sure what can.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Volume 33, Issue 2-3, June 2010 pp 61-83

http://journals.cambridge.org.simsrad.net.ocs.mq.edu.au/action/displayAbstract?aid=7825833

Abstract

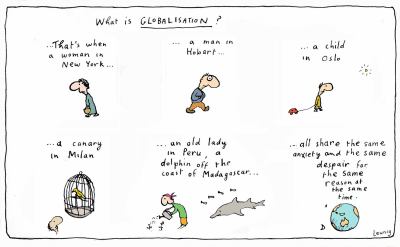

Behavioral scientists routinely publish broad claims about human psychology and behavior in the world’s top journals based on samples drawn entirely from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. Researchers – often implicitly – assume that either there is little variation across human populations, or that these “standard subjects” are as representative of the species as any other population. Are these assumptions justified? Here, our review of the comparative database from across the behavioral sciences suggests both that there is substantial variability in experimental results across populations and that WEIRD subjects are particularly unusual compared with the rest of the species – frequent outliers. The domains reviewed include visual perception, fairness, cooperation, spatial reasoning, categorization and inferential induction, moral reasoning, reasoning styles, self-concepts and related motivations, and the heritability of IQ. The findings suggest that members of WEIRD societies, including young children, are among the least representative populations one could find for generalizing about humans. Many of these findings involve domains that are associated with fundamental aspects of psychology, motivation, and behavior – hence, there are no obvious a priori grounds for claiming that a particular behavioral phenomenon is universal based on sampling from a single subpopulation. Overall, these empirical patterns suggests that we need to be less cavalier in addressing questions of human nature on the basis of data drawn from this particularly thin, and rather unusual, slice of humanity. We close by proposing ways to structurally re-organize the behavioral sciences to best tackle these challenges.

Article summary

If you absolutely don’t want to read the target article (you should), I’ll also provide a bit of summary discussion to supplement the abstract. Skip ahead to the next section if you just want my response.

Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan first survey some of the evidence that Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic subjects – more specifically, University undergrads – are disproportionately the empirical foundation for claims being made, either explicitly or implicitly, about human nature. The evidence here is pretty staggering, even for someone like me who is suspicious of psychology for precisely this reason.

A recent survey by Arnett (2008) of the top journals in six sub-disciplines of psychology revealed that 68% of subjects were from the US and fully 96% from ‘Western’ industrialized nations (European, North American, Australian or Israeli). That works out to a 96% concentration on 12% of the world’s population (Henrich et al. 2010: 63). Or, to put it another way, you’re 4000 times more likely to be studied by a psychologist if you’re a university undergraduate at a Western university than a randomly selected individual strolling around outside the ivory tower.

Moreover, psychology is disproportionately American, and especially English-speaking, even compared to other scientific fields. 70% of all psych citations originate from US research institutions, compared with 37% in a field like chemistry, and the top four countries for psychology citations are all English speaking.

Despite the skewed sampling, psychologists seldom offer cautionary notes about the source of their data or its potential cultural boundedness, and likely would be testy if the cross-culturally critical among us suggested that they retitle their publications to reflect the source of their information: such as, the Journal of Experimental Psychology in High-Enrollment American Research Universities: Undergraduate Psychology Students’ Perception and Performance, a personal favourite. Henrich and colleagues do a good job of pointing out where there are exceptions to the pattern, and many of the authors of comments have been leaders in trying to implement broader, cross-cultural sampling, but the pattern is pretty pronounced in spite of noteworthy exceptions.

Henrich and colleagues then go on to use existing studies to contrast WEIRD subjects with other sorts of people on a series of increasingly close, ‘telescoping’ contrasts: first, they compare industrialized and ‘small-scale’ societies in areas such as visual perception, fairness, cooperation, folkbiology, and spatial cognition. The authors then highlight the contrast of ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ populations on measures such as social behaviour, self-concepts, self-esteem, agency (a sense of having free choice), conformity, patterns of reasoning (holistic v. analytic), and morality.

The authors then examine how Americans specifically stand out from other subject pools in comparative research to highlight how the specific dominance of US subject pools in psychological research might skew our understanding. In particular, Henrich and colleagues survey the issue of individualism, choice, and other outlying US traits. This section is among the thinnest in the article, but it is still full of suggestive data, especially for those of us who are sensitized to the dissimilarities glossed over in the catch-all term, ‘Western’ (my Australian wife and I, a Yank, frequently find ourselves contending with Oz-Sepo contrasts in daily life, even though Australia and the US would typically be considered quite similar ‘Western’ cultures).

The authors then examine how Americans specifically stand out from other subject pools in comparative research to highlight how the specific dominance of US subject pools in psychological research might skew our understanding. In particular, Henrich and colleagues survey the issue of individualism, choice, and other outlying US traits. This section is among the thinnest in the article, but it is still full of suggestive data, especially for those of us who are sensitized to the dissimilarities glossed over in the catch-all term, ‘Western’ (my Australian wife and I, a Yank, frequently find ourselves contending with Oz-Sepo contrasts in daily life, even though Australia and the US would typically be considered quite similar ‘Western’ cultures).

Finally, Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan contrast the Americans who typically wind up as psychology subjects with the whole population of the US, highlighting the diversity among adult Americans in such area as social behaviour, moral reasoning, cooperation, fairness, performance on IQ tests and analytical abilities. US undergraduates exhibit demonstrable differences, not only from non-university educated Americans, but even from previous generations of their own families.

Herich et al. are careful to point out that ‘difference’ is not the whole story, that there are underlying similarities among the diverse groups, and they are agnostic about the causes of various contrasting results. They suggest (2010: 79) that determining a set of criteria for traits likely to be universals would be helpful to psychology and behavioural science and offer a few examples.

But perhaps the main point is a cautionary one, arguing that the developmental environment for WEIRD children may be statistically unusual in a wide variety of ways from the typical environment of modern Homo sapiens throughout our species’ time on the planet:

The fact that WEIRD people are the outliers in so many key domains of the behavioral sciences may render them one of the worst subpopulations one could study for generalizing about Homo sapiens…. WEIRD people, from this perspective, grow up in, and adapt to, a rather atypical environment vis-à-vis that of most of human history. It should not be surprising that their psychological world is unusual as well. (2010: 79-80)

As a counter-balance to the oddity of WEIRD subjects, and their overwhelming over-representation in psychological research to this date, Henrich and colleagues recommend an ambitious cross-cultural research agenda, changes to publication policy to redress the imbalance, and a range of other practical, albeit quite difficult, policies.

They highlight that adding subjects to our pools may not be sufficient to fix biases that are inherent in research questions, method, or theory, a point that several of the commentators also discuss, some with less optimism than Henrich and colleagues (for example, Gosling, Carson, John and Potter; Shweder; and Baumard and Sperber).

Overall, what most recommends this article is not that these arguments have never been made before, but rather the breadth and depth of the empirical sources that Henrich and colleagues draw into the discussion. For example, Paul Rozin, who arguably has made very similar arguments before, lauds Henrich and colleagues, writing about the message of cross-cultural variation, ‘never has it been so thoroughly documented and elaborated into all the domains in which it is relevant. And never so convincingly’ (2010: 108). High praise, indeed.

So what possible quibbles could I have with a piece that clearly has so much so right? Let the picking of nits begin!

Is being WEIRD really what makes them odd?

Henrich and colleagues use the acronym WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) to capture the distinctiveness of the typical subjects used in psychology experiments – university students in psychology classes – but I suspect that this acronym, however clever, fails to truly capture how odd these subjects are. One could add a host of other terms that would highlight other outlying characteristics of this population, especially differences that may not be so obvious to WEIRD researchers.

Although WEIRD is terribly catchy and quite manageable, it may not even focus us on the most important distinctions, nor may it reflect a good starting point for a truly trans-cultural psychology, carting our own self-conceptions and obsessions, surreptitiously, into the cross-cultural comparisons. Is WEIRD weird enough to constitute a break from typical ways of thinking among the WEIRD researchers? (God, this if fun. It’s one reason I think the article has legs: rhetorical catchiness.)

For example, when I brought one of my Brazilian subjects to an American university at which I previously taught, his characterization of the American students’ differences from young Brazilians with whom he had more contact focused on none of these traits (W. E. I. R. or D.). He was more struck by their large size (both height and BMI, to put it nicely), their frumpy androgynous clothing (anyone here not wearing a sweatshirt?), their materialism, their clumsiness and physical ineptitude, and their ethnic and personal homogeneity. If my Brazilian colleague were to characterize the oddness of the WEIRD, he wouldn’t focus on the traits Henrich and colleagues have chosen in their designation.

From the perspective of my admittedly non-academic Brazilian colleague, the truly outstanding characteristics of the US students were characteristics like their body types, the diminishing of gender markers, and the evidence of extraordinary peer-group conformity in bearing, expression and personal presentation. His observations are hardly scientific, but they suggest that focusing on ‘Western-ness’, education, economic system, wealth, and political system certainly doesn’t exhaust the parameters of difference and it might not even highlight the most salient, although it does correspond to patterns of the Big Variables in Western scholarship about difference (when I was in grad school, it was the Holy Trinity: gender, class and ethnicity).

I don’t think that my point is a fundamental disagreement with Henrich and colleagues, but a concern that the parameter of difference we choose to highlight, even in the simplest designation, might itself be a culturally-generated bias. Anthropologists are well acquainted with having our subjects point to traits that are invisible to the Western research as ‘the crucial’ characteristic for understanding the gap. For example, ‘rich’ may seem an obvious contrast to poverty, but we know that not all ‘poverty’ is the same, nor are all ‘rich’ people able to experience in the same way their material situation. Some economists have argued that inequality is more crucial for understanding the experience of deprivation, for example, than absolute wealth. And poor populations often fix, not on their material deprivation, but on other qualities to describe their difference from the wealthy (or the WEIRD). For example, religious differences, family dynamics, or caste might be salient to people from other cultural backgrounds.

In addition, I worry that some of our cultural ideology and self deception may be smuggled in under the terms themselves, especially ‘Western,’ ‘industrialized’ and ‘democratic.’ ‘Western’ has been too comprehensively discussed to really dwell on here, but I’m struck by both ‘democratic’ and ‘industrialized’ as forms of self description for Americans, especially. After all, isn’t ‘de-industrialization’ or post-industrialization a key economic transformation in the United States, and aren’t many American commentators worried about the hollowing out of ‘democracy’ in an age of voter apathy and corporate domination of media and political lobbying?

If WEIRD college students aren’t voting in large numbers, for example, and feel profoundly alienated from politics, isn’t it problematic to think of ‘democracy’ as shaping their attitudes? I’d be more inclined to say we should examine the landless farmers in Brazil I worked with while studying the Landless Movement to understand ‘democratic’ populations. They had long community meetings modeled on the labour movement or anarchist movement to come to decisions. I doubt my university students in the US had experienced anything nearly as ‘democratic.’

Again, I think that my critique is more than a bit unfair, as Henrich and colleagues are writing for an experimentalist academic community that needs to be made aware of the distortions introduced by accustomed research methods. They’re not writing for an audience of deconstructivist, left-leaning, post-colonial political economists, anthropologists, or cultural studies scholars. My ‘critiques’ are more about how we might shepherd the next stage of research if Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan are successful with their intervention. I worry that, even if psychologists, brain scientists, and evolutionary theorists decide that they need to take human variation seriously, anthropology isn’t going to be ready as a discipline to help (one more reason I appreciate the inter-disciplinary program that Henrich and his colleagues are sketching).

So, to sum up this post-Henrich, next stage concern: I worry that W.E.I.R.D. classification flatters the WEIRD, focusing on traits that Westerners typically highlight to describe themselves in ways that are, however inadvertently, pretty self-congratulatory. If we were to call the same group, Materialist, Young, self-Obsessed, Pleasure-seeking, Isolated, Consumerist, and Sedentary (MYOPICS)… you get the idea. (By the way, I’m not committed to this, only to getting my own acronym – You know the steps in the cheap acronym process: Set acronym. Find words to fit each letter.)

How the WEIRD get weird

Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan are really good in the target article to refrain from too much speculation about the explanations for the peculiarity of the WEIRD. It’s one of the many things that I think they need to be congratulated on, and their openness invites a wide-ranging discussion of the many likely contributing facotrs. But many of the specific qualities highlighted in the Henrich et al. piece and in the responses likely do not stem directly from being either W., E., I., R. or D., so the classification itself can be misleading.

For example, one of the prime candidates for the cause of some of the measurable differences is variation in child-rearing techniques, especially forms of verbal interaction with infants and young children, their visual and sensory environments, and the manual forms of care given to children. WEIRDness doesn’t necessarily determine this childhood environment, even though many childcare practices that might help to create the psychological statistical anomalies we find in these populations do correlate with being WEIRD. If English is affecting how the WEIRD think in ways that make them unusual, for example, there’s no inherent reason why English speaking-ness necessarily leads to WEIRDness, although the WEIRD are disproportionately English-speaking (especially those surveyed for psychological research).

For example, one of the prime candidates for the cause of some of the measurable differences is variation in child-rearing techniques, especially forms of verbal interaction with infants and young children, their visual and sensory environments, and the manual forms of care given to children. WEIRDness doesn’t necessarily determine this childhood environment, even though many childcare practices that might help to create the psychological statistical anomalies we find in these populations do correlate with being WEIRD. If English is affecting how the WEIRD think in ways that make them unusual, for example, there’s no inherent reason why English speaking-ness necessarily leads to WEIRDness, although the WEIRD are disproportionately English-speaking (especially those surveyed for psychological research).

Again, this is not so much a critique of Henrich and colleagues but a consideration of where we go from here, how we get at human psychological variation. The point is just that it will not be enough to try to get populations who are different to Us (if You, the reader, are WEIRD) in ways that we recognize. For example, although poor populations within Western countries may demonstrate significant variation, they might not, and not because variation is not possible; they might share child caring practices with wealthier countrymen without sharing wealth or income profile. The choice of comparison should be motivated by the research question and hypotheses about relevant causal dynamics, not simply, like the broader reliance on WEIRD subjects, the result of convenience in sampling.

Who you callin’ ‘SMALL-scale’!?

Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan use the term ‘small-scale,’ although they are very clear what the term means and that it is not a thin proxy for ‘primitive’ (see p. 123, fn#4). I’m more than a bit uncomfortable with the term ‘small-scale’ although it is arguably the most acceptable classification for the groups that are being clustered (and miles and miles and miles better than ‘primitive’ and other bare-facedly ethnocentric terms). The problem is, what’s the contrast with ‘small-scale’? If it’s ‘Western,’ than we have an asymmetrical binary distinction where some groups will arguably fall under both categories or under neither.

For example, ‘small-scale’ focuses on a cluster of traits that don’t NECESSARILY co-vary, although they might in until-recently foraging groups: small, geographically-bounded groups with slight division of labour, local organization through kinship, self-sufficient in food provisioning, and face-to-face interaction. The obvious ‘none of the above’ cases in the ‘small-scale v. Western’ contrast are non-Western groups who are not small-scale, such as city dwellers in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Pacific (outside Australia and New Zealand). This group would constitute a substantial part of the world’s population, if not the largest grouping.

And what about Western populations living in small-scale settings? For example, I live in a very wealthy town of around 2000 people where I frequently encounter people I know on the street. As members of a gentrified country town, we grow and eat a lot of local produce, more so every year for ideological reasons, and, given 5 or 10 minutes, most of the locals can find kin or age-cohort connections in a process that is as seemingly obligatory as it is tedious for a ‘blow in’ (local argot for an in-migrant) like myself to watch. I’m surrounded by people interested in green lifestyles, self-sufficiency, ‘slow food,’ reconnecting socially – many of them living on million-dollar properties. We’re obviously WEIRD – waaaaaay WEIRD – but also, in an admittedly tendentious argument, ‘small scale.’

I don’t think for one SECOND that Henrich and colleagues are not aware of this issue, but I think that the problem highlights a stumbling block for anthropologists doing cross-cultural comparisons more generally: the use of binary classifications is likely to be a nagging intellectual handicap. Much more useful is to really think through Henrich’s suggestion, in the same footnote (p. 123, fn#4), about an ‘n-dimensional’ comparative space for talking about cultural distinctions.

The contrast of ‘small-scale’ to ‘Western’ seems to me to be an artifact of more simplistic forms of cross-cultural comparison, more ‘primitive’ intellectual projects than the one Henrich and colleagues are proposing. So much of the discussion in the article, including the really intriguing graphs showing the wide range of variation WITHIN both WEIRD and ‘small-scale’ groups, runs counter to the dichotomy, highlighting the fact that human diversity can’t be too quickly recuperated with old-fashioned Us-Them thinking. I don’t think Henrich and colleagues fall victim to bipolar thinking as an intellectual short-cut, but I worry that there’s dead-falls lurking along the path of the terminology itself.

My own candidate for one source of the oddity

Although Henrich and colleagues are laudably restrained in speculating about the sources of differences between WEIRD populations and other groups, I want to put another candidate on the table that’s discussed by Lana B. Karasik, Karen E. Adolph, Catherine S. Tamis-LeMonda, and Marc. H. Bornstein in one of the responses that I enjoyed a lot. They talk about ‘WEIRD walking,’ the way that WEIRD populations are also outliers in terms of motor development in ways that many people in the field overlook.

Karasik and colleagues describe how WEIRD children’s patterns of motor development became enshrined in psychology through testing procedures, test items and norms into an understanding of universal ‘stages’ of motor development (see 2010: 95). Even when cross-cultural research was conducted, these culturally-specific criteria, derived from examining WEIRD developmental pathways, meant that researchers were often carrying with them tools that were ill-suited to study other sorts of children. Or these psychologists were simply comparing diverse children to WEIRD ones on standards set by the WEIRD children.

Karasik and colleagues describe how WEIRD children’s patterns of motor development became enshrined in psychology through testing procedures, test items and norms into an understanding of universal ‘stages’ of motor development (see 2010: 95). Even when cross-cultural research was conducted, these culturally-specific criteria, derived from examining WEIRD developmental pathways, meant that researchers were often carrying with them tools that were ill-suited to study other sorts of children. Or these psychologists were simply comparing diverse children to WEIRD ones on standards set by the WEIRD children.

One example of this that I have discussed is overhand throwing, a task that has been used in some tests of motor coordination in spite of the fact that different cultural groups demonstrate enormous variability in the activity because it is a skill, not a universally-acquired entailment of being human. Some children learn to throw in environments that support, model and reward the activity; others never really learn to throw particularly well because their activity patterns simply do not include the opportunity to learn (I’ve written in a book chapter that will soon appear about ‘throwing like a Brazilian,’ an analogue to ‘throwing like a girl’).

Karasik and colleagues point out that even such ‘basic’ motor abilities at crawling are susceptible to manipulation: the trend to put newborn children on their backs to sleep in the West, for example, has retarded the development of crawling in a population where children formerly would routinely sleep on their bellies. In some groups, normal development may not even include crawling, children skipping the stage entirely or using some other intermittent form of locomotion, like ‘bum-shuffling’ or scooting about while seated.

In my own research, the physical abilities of WEIRD university students stand out more clearly as strikingly odd than many of their other traits, and I’m convinced that the extraordinary inactivity of this population, coupled with their high calorie diets, has more diverse and wide-ranging effects than simply leading to an epidemic of obesity, Type-II diabetes, and other diet-related health problems. For example, capoeira instruction, a subject close to my heart, has to start at a much different place for American youth than it does with Brazilian kids in Salvador where I did my field research. Even teaching salsa lessons at a Midwestern US university drove home the profoundly different motor starting point, prior to the lessons, of young adults in the US compared to Brazilians (and I suspect, to many populations in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and elsewhere).

The point is not just to rehearse the typical alarmist discussion of the ‘obesity epidemic,’ but also to point out the profound potential implications of radical differences in activity environments for children during their development. I don’t think most WEIRD theorists realize just how powerful an influence sedentary living is on our psychological, physiological, metabolic, endocrine, and neural development because most of us, subjects and researchers alike, are SO sedentary. WEIRD bodies have so much unused energy from their diets, especially with their levels of activity plummeting, that I find it hard to believe we understand metabolic patterns that would have dominated much of human prehistory.

To argue that WEIRD subjects are a good window in on ‘human nature’ is difficult when, from the perspective of metabolic energy and expenditure, the WEIRD are such outliers in the whole history of our species. We know that this radically unusual metabolic situation — massive energy surplus with less and less expenditure — is profoundly affecting mortality patterns: in WEIRD societies, most of the leading causes of death are, arguably, directly linked to the human body’s difficulty of coping with this situation, and that’s even after generations of sedentary life in which to adapt. But the psychological and neurological consequences of sedentarism are less well understood in part, in my opinion, because most WEIRD researchers have a hard time even imagining how arduous life would have been. Throughout human existence, most humans likely have been phenomenally active, and athletic, compared to WEIRD populations, out of necessity.

I’m going to have to write something more in depth on this, but I just feel the need to flag it. If I had written a response, I probably would have focused on this trait because it runs against WEIRD researchers’ self understanding. The WEIRD tend to think of themselves as unusually healthy, and by measures of things like infectious disease rates, death from accident, and infant mortality, they certainly are. But from a broad, cross-cultural view, the extraordinary inactivity of the WEIRD, coupled with their access to very energy dense, highly processed food sources, makes them outliers in ways that I’m not sure we fully comprehend.

Taking issue with some of the responses

A number of the commentators bring really interesting points to the discussion. A few that I have to single out for special praise are Majid and Levinson on WEIRD languages; Leavens, Bard and Hopkins on BIZARRE chimpanzees (the acronym thing is apparently contagious); Karasik and colleagues on motor development; Chiao and Cheon on brain imaging; Ceci and colleagues on hiccups in research design; Fessler on unknown unknowns in shame research; Lancy on ethnocentrism in child development research… There’s really a lot of great discussion, most of it building upon what Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan have laid out in the target article. Again, I can only really recommend that you read the original.

That said, there are a couple of responses that I have to take issue with, including a couple that Henrich and colleagues handle far more diplomatically than I would have.

‘Difference is really uniformity if you just ignore difference’

Lowell Gaertner, Constantine Sedikides, Huajian Cai and Jonathan D. Brown basically write a piece that says, ‘yeah, yeah, differences, differences, yada yada…. But the over-arching human universals, the kind that we label with vague generalities that could be applied to anything, are really the point, and they’re GENETIC!’ Frequent readers of our weblog will know that this kind of argument gets me as hopped up and raving as a post-Halloween kindergarten class. (And don’t even get me started on errant use of the word, ‘reify’…) Danks and Rose offer a similar, but less objectionable use of this argument strategy, suggesting that universality is in the learning process, not in what is learned.

Henrich and colleagues do an excellent job of shredding the specific empirical case made by Gaertner and colleagues about the universality of ‘positive self-views’ (see esp. pp. 119-121), so I won’t dwell on the nuts and bolts. Flogging a dead horse and all. What I just want to highlight is that the idea that there is something ‘essential,’ an obdurate and universal ‘human nature,’ is NOT evolutionary thinking. To argue against ‘human nature’ is not to be anti-evolutionary.

For some reason, some (though not ALL) theorists try to make the argument for human variation appear to be against evolution, which is something I can NOT understand, except in the narrow confines of the history of feuding within anthropology. Even in my freshman human evolution course, one of the key arguments from Week Two is that even Darwin’s classical perspective on natural selection says that species change and that variation is a fundamental precondition for natural selection even if stabilizing selection produces patterns of continuity over time.

But the bigger problem with Gaertner et al. is the common assumption that, although there’s diversity in ‘behaviour’ or ‘phenotype,’ on some other higher level of abstraction, there’s unity, even if that unity has to be stated in such vague terms that it’s essentially meaningless. Likewise, I’m not convinced that Danks and Rose are on solid ground, or making much progress by trying to separate out learning processes from what is learned, and then to argue that the processes are universal. As an empirical statement, the argument for universal learning processes is obviously false. Some societies, like WEIRD ones, have extensive, explicit, segregated systems for formal learning; others have virtually no separate contexts for learning or have very different sorts of institutions than classrooms.

I just don’t think I get why some theorists must, as soon as confronted by evidence of diversity, immediately declare that there’s ‘uniformity,’ at some ‘higher level’ of abstraction. The act can often sound like a vague rearguard defense, as if there is some underlying need to demand uniformity in spite of evidence to the contrary. For example, confronted by the empirical reality of profound dietary variation in humans, of survival for multiple generations at near starvation levels, of culturally-induced dietary restrictions, of eating patterns that are unhealthy and self-destructive, even voluntary self-starvation or gross over-consumptions, some defenders of universalism, like Gaertner and colleagues say, ‘the diverse diets are connected and assimilated by a universal need for sustenance’ (2010: 93).

The point is not that there are no universals; it’s that the ‘assimilation’ of diversity into a meaningless ‘universal’ is a hollow exercise that seeks to escape from the very point that Henrich et al. are marking. Gaertner and colleagues argue that apparent, empirically-verifiable diversity is actually unity at an ‘abstract process and function’ level, a retreat to an unfalsifiable and ineffable assertion, especially when coupled with allusions to ‘genotype’ that also can’t be shown to be empirically founded. Even absolute, empirically demonstrated universality is NOT proof that something is ‘human nature’; everywhere on Earth, humans deal with gravity, but this is not due to ‘human nature,’ except that to be a human is, like all other matter, to have mass affected by gravity.

It would be alright, logically, to retreat to universal declarations about human universals of process or function ONLY IF the psychologists who made this retreat would then refrain from making any statement or implying any characterization of humans more specific than that abstract universalism. In other words, if you’re going to argue that the universal trait is the need for sustenance, than you have to stop yourself from making pseudo-evolutionary arguments about food preferences for salt-and-vinegar potato chips, fizzy soft drinks, and ‘death by chocolate’ cake, or anything else. That is, you can’t strategically retreat to abstract high ground as soon as you’re challenged empirically on sloppy universalisms only to boldly foray forth into the land of blanket statements about more detailed characteristics of ‘human nature’ as soon as you think no one is watching.

It would be alright, logically, to retreat to universal declarations about human universals of process or function ONLY IF the psychologists who made this retreat would then refrain from making any statement or implying any characterization of humans more specific than that abstract universalism. In other words, if you’re going to argue that the universal trait is the need for sustenance, than you have to stop yourself from making pseudo-evolutionary arguments about food preferences for salt-and-vinegar potato chips, fizzy soft drinks, and ‘death by chocolate’ cake, or anything else. That is, you can’t strategically retreat to abstract high ground as soon as you’re challenged empirically on sloppy universalisms only to boldly foray forth into the land of blanket statements about more detailed characteristics of ‘human nature’ as soon as you think no one is watching.

What I don’t get, I guess, is the defensiveness. Are the knee-jerk universalists worried that, if we concede that there might be fundamental variation in humans, we inevitably move toward racism? If so, we’re in trouble. Do they think that the existence of human genes means that we must necessarily be a species of genetic clones? Are they worried that science can’t be conducted on a topic where one cannot make blanket universalizing declarations? If so, someone should tell biologists because they’re in trouble. Is it just intellectual laziness? Or is it a fear of some previous intellectual error, like the denial of science itself, committed by some intellectuals in the name of diversity? I suspect that it might be the last, but, unfortunately, it often sounds like one of the earlier objections.

I don’t have a problem with saying there are some universals; I just have a problem with someone, when confronted with evidence that a particular trait is NOT universal, immediately trying to declare that it really, really is uniform if we just squint our eyes, blur our understanding, and step back further from the object of study. What’s the point?

You say WEIRD, I say nuh-uh!

I’d also take issue with Paul Rozin’s commentary, although I think he makes some excellent points (and I very much respect his work). My main problem is the assumption that technologically-driven human development will necessarily lead the world to become, well, WEIRDer:

But the main point of my commentary is that although the NAU [North American undergraduate] is truly anomalous, this subspecies of Homo sapiens is a vision of the future. With the Internet, ready availability of information of all sorts, computer fluency as key to success in the world, and ease in negotiating a world where text as opposed to face-to-face interactions are the meat of human relationships, the NAU is at the vanguard of what humans are going to be like. (Rozin 2010: 109)

Perhaps I just don’t share Rozin’s techno-optimistic ‘vision of the future’ online as a species, but Rozin seems to assume that the wealthiest, most well educated, most privileged and greediest resource-consuming sliver of the world’s population is just a bit out in front temporarily from where everyone will eventually arrive. Someday, when we grow up as societies, we’ll all be like college students. God save us if that’s the case, because the environmental footprint is going to be catastrophic unless a lot changes in the next few years.

Perhaps I just don’t share Rozin’s techno-optimistic ‘vision of the future’ online as a species, but Rozin seems to assume that the wealthiest, most well educated, most privileged and greediest resource-consuming sliver of the world’s population is just a bit out in front temporarily from where everyone will eventually arrive. Someday, when we grow up as societies, we’ll all be like college students. God save us if that’s the case, because the environmental footprint is going to be catastrophic unless a lot changes in the next few years.

I don’t think I’d be alone in my suspicion that this view of digital ‘modernization’ is reminiscent of many declarations that some new technology was going to change us fundamentally as a species; so far, I think the evidentiary ball is in the court of the techno-optimists to write a plausible account of how that will happen. Just as some might argue the world is getting WEIRDer, others might argue that the Western nations are less uniformly WEIRD.

I’d also take issue with Alexandra Maryanski’s commentary, but I’m just not really sure I get where she’s coming from, so I don’t know where to start (Henrich and colleagues don’t respond at length to this piece). On the one hand, Maryanski seems to be aware of cross-cultural research; on the other, I’m not sure she’s really read it the same way that I would. The piece is so shot full of rhetorical questions that it’s hard to follow the logic, but she seems to be saying that, because ethnographic data on hunter-gatherers says that they have ‘high individualism, reciprocity, and low levels of inequality,’ then WEIRD societies are sort of just like the societies in which humans first evolved…

For, despite all the multiple ills of industrialized societies, WEIRD societies may be more compatible with our human nature than the high-density kinship constraints of horticultural societies or the “peasant” constraints of agrarian societies with their privileged few

So, people in industrial societies are JUST LIKE hunter-gatherers, except for the gigantic scale, anonymous interaction, replacement of reciprocity-based relationships with market transactions, and the unprecedented-in-human-history levels of material inequality. (For the slow readers, yes, that’s irony.) Oh, and the domestication of plants and animals, sedentary settlements, high technology, extended classroom education, mass media imagery, enormous social institutions, changes in family structure, decrease parent-infant contact, radically new built environment, completely different, dense social structure…

That’s why I say that, although there’s evidence that she’s aware of the Human Relations Area Files, I’m just not sure how Maryanski read them to come away with the impression that the WEIRD are just like the foraging peoples in the ethnographic record. Maybe the train just left the station without me on this argument, but I do not get it.

The argument she MIGHT make is that, with the enormous proliferation of technology and division of labour, WEIRD humans, especially in the extended adolescent period created by the system of tertiary education that delivers them as subjects to psychology researchers, demonstrate what humans might be like if they were utterly REMOVED from most normal selective pressures. If anything, university students might be demonstrating the utter nihilism and lack of restraint when normal external scaffolding on human behaviour and decision making are relaxed and replaced with fermented motivation, collective peer effervescence, and complete discounting of any future outcomes…

The argument she MIGHT make is that, with the enormous proliferation of technology and division of labour, WEIRD humans, especially in the extended adolescent period created by the system of tertiary education that delivers them as subjects to psychology researchers, demonstrate what humans might be like if they were utterly REMOVED from most normal selective pressures. If anything, university students might be demonstrating the utter nihilism and lack of restraint when normal external scaffolding on human behaviour and decision making are relaxed and replaced with fermented motivation, collective peer effervescence, and complete discounting of any future outcomes…

Might make that argument.

I’m not sure I’m persuaded by it, but maybe slavish obedience to peer pressure, high levels of inebriation and pizza consumption, cluttered living spaces, transitory sexual relationships, intermittent high-stress all-nighters punctuating months-long periods of sloth-like inactivity except for feeding, drinking and playing video games – maybe this is in fact what humans choose to do when divested of all responsibility for themselves with virtually no immediate pressures except for self-created social ones. Or maybe I’m just describing my own time in college.

Concluding thoughts

I apologize for this overly long discussion, especially in a blog format, but I just feel terribly inspired by this piece by Henrich, Heine and Norenzayan. I can’t thank the authors enough, and I am going to learn how to use a citation tracker specifically so that I can follow the subsequent impact of this article.

My reservations notwithstanding, I think it’s a remarkable piece, one that really needed to be written, and I congratulate the authors on it. It’s a thorough, well-thought piece, but with the added advantage of having some especially well-chosen examples and that colossal, infectious, acronymic hook, the glossy term that captures such a key idea well. I think the piece will travel well and might actually have a terribly salutary effect on the WEIRD populations it is targeting.

References discussed:

Arnett, J. 2008. The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist 63(7): 602-14.

Danks, David, and David Rose. 2010. Diversity in representations; uniformity in learning. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 90-91. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000075

Gaertner, Lowell, Constantine Sedikides, Huajian Cai, and Jonathon D. Brown. 2010. It’s not WEIRD, it’s WRONG: When Researchers Overlook uNderlying Genotypes, they will not detect universal processes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 93-94. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000105

Henrich, Joseph, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan. 2010. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 466(1): 29.

Henrich, Joseph, Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan. 2010. The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 61-135 (with commentary). doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X Check Joseph Henrich’s homepage for a pdf of the article and related audio files.

Karasik, Lana B., Karen E. Adolph, Catherine S. Tamis-LeMonda, and Marc H. Bornstein. 2010. WEIRD walking: Cross-cultural research on motor development. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 95-96. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000117

Maryanski, Alexandra. 2010. WEIRD societies may be more compatible with human nature. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 103-104. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000191

Rozin, Paul. 2010. The weirdest people in the world are a harbinger of the future of the world. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 108-109. doi:10.1017/S0140525X10000312

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

I met a psychologist once who always pooled results from males and females in his studies (he’s a teacher at my school.) After talking to him about it, it turns out that he was convinced that an adequate way to deal with the differences between men and women is simply to ignore them! It’s a frustrating tendency.

I’m a bit aghast at the apparently common use of the term “human nature” in this discussion. It just seems outdated and a bit inaccurate to me – if we believe in evolution, we don’t really believe that humans have the sort of unchanging, inherent, morally privileged essence that the term implies. I honestly didn’t think that anybody would still use it with a straight face.

This whole thing reminds me of The Snark was a Boojum by Frank Beach ( http://www.sfn.org/skins/main/pdf/HistoryofNeuroscience/FrankABeach.pdf ), which described the same sort of phenomenon in experimental psychology. Psychologists were using a few strains of albino rats, and attempting to make inferences about the behavior of animals in general.

I’m middle aged now. And I never got the sense that the term “human nature” inherently, necessarily, and entirely implied a belief “that humans have the sort of unchanging, inherent, morally privileged essence”.

Many people seem to recognize that the human species expresses a wide variety of psychological and behavioral patterns. And my sense is that is what most people mean by “human nature”.

Human potential, if immense, is not infinite. It still follows typical patterns in most cases, as shown in social science research. Similar to the false dichotomy of nature vs nurture, the issue of human potential not a dualistic either/or scenario.

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2015.0071

Thank you for this in-depth response. I suppose that i am part of the intended audience for this (being an experimental psychology phd) and while I read the article on preprint, I havent yet read the commentaries.

Thanks for the review and the suggestions around the article.

If you truly believe that there are no universals in the human psyche, then it follows that the entire nomothetic enterprise of psychological research is useless — not just its focus on Westerners. That is clearly false, however, given that psychological research conclusions have demonstrable real-world utility. Furthermore, mean differences on constructs among naturally formed demographic groups are less relevant (and more variable) than patterns of interrelationships among constructs, which have been the main focus of psychology since the 1950s.

As important as is WEIRD bias, your criticism was basically my own immediate response to that particular issue. Social science research could tell us nothing if every human individual literally was unique in all ways with no shared species traits, behavioral patterns, motivations, cognitive biases, etc.

Imit, you didn’t really read the post, did you? Greg and Henrich et al. are not against the idea of universals per se, but that we tend to assume universals where really there is much more diversity than appreciated, and the data show that.

So here are two choice quotes: “Henrich et al. suggest (2010: 79) that determining a set of criteria for traits likely to be universals would be helpful to psychology and behavioural science and offer a few examples… “ and “The point is not that there are no universals; it’s that the ‘assimilation’ of diversity into a meaningless ‘universal’ is a hollow exercise that seeks to escape from the very point that Henrich et al. are making.”

You do the same – you just assert the real-world utility without showing it, and you claim “naturally formed demographic groups” out of what are social groups, formed by history and by our concepts of what goes together.

As Greg’s Brazilian friend saw, Americans are very homogeneous, and in not flattering ways, and yet some psychologist could set out to study the inter-relationships among the Brazilian’s main views and come up with some very useful, and very judgmental, conclusions about how bad off Americans are psychologically. The Brazilian wouldn’t do this, but the American psychologist would often assume that this then applies around the world – after all, humans form one group, right?

Greg had a great post Exporting American Illness, which was a review and comment on Ethan Watters new book, Crazy Like Us: The Americanization of Mental Illness, which makes that basic argument.

Your point about psychologists studying patterns of interrelationships among constructs is valid. But again it misses the point of WEIRD and what Greg says – that we develop constructs based on what we think is relevant to “human psychology” writ large, and we end up then saying these patterns hold true around the world, since it’s been easy to get data from university students in several different very developed countries.

Both the conception of the constructs and the actual data samples are skewed, the first by the dominant position and odd cultural traits of Americans and the second by choosing ease of access and replicability over actually engaging real-world diversity.

So here’s a new set of constructs: “Materialist, Young, self-Obsessed, Pleasure-seeking, Isolated, Consumerist, and Sedentary (MYOPICS)…” Though actually demographically the rest of the world is much younger than Western countries, so I might suggest “Youthful” with a need to focus on the relationships between Y and O to get at our obsession with youthfulness…

This article asserts that, “What I just want to highlight is that the idea that there is something ‘essential,’ an obdurate and universal ‘human nature,’ is NOT evolutionary thinking. To argue against ‘human nature’ is not to be anti-evolutionary.”

As far as I can tell, that couldn’t possibly be true if interpreted in absolute terms and, indeed, no qualifications are added there. Even in confronting the WEIRD bias, we still do find what appears to be more or less essential and universal in the human species across populations: hyper-imitation, cooperation, collaboration, pro-sociality, and theory of mind.

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.2015.0071

Greg, thank you for a blog post actually worth reading, as is always the case with yours. I was struck by your use of the term ‘salient.’ It might be worth your time to look at the concept of sociolinguistic salience—dialect and class distinctions are invariably based upon rather piddling (as far as semantics and linguistic structure go) differences in usage. They in fact have to be, as almost no one possesses the natural tendency or training to do real linguistic analysis. (But, hey, if busting people for their double negatives makes you feel smarter go right ahead. I personally feel smarter than you because double negatives don’t confuse me…)

Touché, Msr. Bradley, I must not be non-gracious so much. And not becoming unconfused is hardly not my non-normal state, if you know what I mean.

But I do know what you mean about salience . I’m still trying to get my fake Aussie accent together, and I’m having a terrible time, even though I’m perpetually surrounded by models theoretically. Astonishing how minute the salient details are perceptually when it’s virtually impossible for me to then perform them when I want.

The one speech quirk that kills me though — and it’s along the line of double negatives is why I bring it up — is the addition of the word ‘but’ on the end of a clause, with nothing following out, to signal that a phrase is unexpected, instead of putting the conjunction at the onset of the phrase. For example, my wife will say something like, ‘That wasn’t what I expected, but.’ It sounds like some sort of pidgin grammatical structure to me. I can’t figure it out, but.

After I posted this I started to wonder if there is a clear difference between the sort of salience that the general public is expected to be aware of (things like double negatives) and those things which are salient to more delimited groups. A non-linguistic example would be whenever I see a guy who keeps going with the queixada and I think, “Soon to be on his back…” while most people probably think, “Wow, cool and dangerous!”

The one linguistic (written, in this case) quirk that gets to me is the use of scare quotes by anthropologists. It’s like the author is telling me, “Yeah, I’m that kind of cultural anthro.”

I would have to hear it in context and get the intonation, but it sounds to me like it might be a tag question. (She’s a looker, innit? Une petite mystère, n’est pas?)

“But” at the end of a sentence is a quirky way of using “though” – e.g. “I don’t think much of that article but!” equates to “I don’t think much of that article though.”

“But” is plosive and ‘stronger’ than “though”, and, as such, it conveys a measure of diffidence without an accompanying eagerness to examine the grounds for that diffidence: the diffidence is acknowledged as taken-for-granted and therefore, by virtue of the implicit claim that it needs no examination, proposed as grounds for commonality between the speaker and the audience. I don’t think it’s an accident that Australians use “but” this way, given the culture of mateship. “But” used in the way you describe is pretty much an invitation to participate as an insider (and to have one’s own – vestigially, though constantly, doubtful – status as such also thereby acknowledged).

I have always worried about sampling issues in journal articles and reseach. However they almost always have a caveat about the limitations due to the sample population. The real problem is how to do studies using less accessible populations. It is easy to do research with college students. It is really hard to do research with homeless people. Now there is a long history of enthographic reseach also using both emic and etic designs. So non-WEIRD reseach is out there. The trick is not to assume any single reseach tells you the answer. The next goal is aggregating college research with ethnographic studies in a meta-analysis studies if you want ideas about the general population. Conversely my statistics training also tells me that narrow research is almost always going to be more robust than broad research questions. So combining lots of narrow studies seems to be the answer, except you get cumulative errors as you add more in more factors and transform various scores to compare. So there is also a statistical limiation here. I can do broad research, which gives me only vague general results or I can combine lots of narrow research and my error rate goes up. So the problem is more complex than just regulating your sample population.

“Western,” as generally understood, is no more a cultural concept than, e.g. “African” is a taxon in biological taxonomy. It’s a geopolitical concept with a bunch of ideologically-driven baggage about culture. I discuss this in Is Western Culture an Illusion?

All social constructions are, well, socially constructed. That is true of ethnicity, race, class, etc. Even much of gender, such as work divisions, is socially constructed. In traditional societies, there all kinds of diverse gender social constructions, such as third spirits.

Interestingly, even the lone male hunter is a social construction. Before the spread of the bow and arrow, humans mostly hunted megafauna. It required all of the tribe, men and women, to hunt together to stab the animal to death. Tool use has powerful implications.

Re: different motor abilities and teaching dance: I’m a Spanish amateur bellydancer. I began dancing in an American school, where I went from level 1 to level 3 (level 4 was professional) in a matter of an academic year. I wasn’t a particularly good dancer, as I discovered later. It’s just that I was generally more aware of my hips and my middle section than the average American my age. It was the most visible example of the difference between American culture and mine.

That is an interesting issue, and complex. Any number of factors would be causal or contributive. WEIRDos spend inordinate amount of time reading, researching, studying, etc; both for education and later careers. This requires them to sit immobile for long hours, from childhood to adulthood. The investment it takes to become fully WEIRD might involve tremendous sacrifice of physical health.

But I suspect that the malnourishing standard American diet (SAD) plays a major role as well in maldevelopment and stunted development. As far as that goes, differences in diet and nutrition would alter all aspects of physical development, not only athleticism, coordination, balance, reflexes, etc but also neurocognitive ability, psychiatric health, personality traits, and who knows what else.

Another related factor would be the psychoactive substances (over-the-counter, prescribed, and illicit) that WEIRDos take to make it possible to sit still for so long while maintaining focus and concentration. That is why stimulants are so popular, from caffeine to Ritalin, with the energy drink market exploding. Then after a day buzzing on stimulants, so many WEIRDos need suppressants like alcohol or sleeping pills to shut their minds down at night.

Involved in this is not only what has been added to our lifestyle but what was taken away. One early 18th century northern Englander, was asked why the fairies disappeared. He said it was because caffeinated teas replaced the traditional groot (or gruit) ales. One commenter noted that groot ales commonly had as ingredients mildly psychedelic herbs. That period of the early 19th century was also the first period of dependable grain surpluses, along with mass urbanization, literacy, and education.

The stimulants like caffeine and cocaine helped many many workers, including the first major wave of WEIRDos, to work the long hours that capitalism required. Without such stimulants, all of modern capitalism might’ve been impossible or else severely constrained. And it was the capitalist markets that made sure there was cheaply available not only plenty of stimulants but also sugar to keep brain workers fueled; well, factory workers too.

The difference for non-WEIRD populations might simply be that all of this was introduced so much later, in some places still not fully introduced. Even in the West, some of these changes are recent. Think about how most Americans, including the working class, now work jobs that require little physical exertion. But within living memory, most Americans had not only jobs but lifestyles that were heavily active. Not that long ago few Americans exercised because they weren’t sitting around most of the time.

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/01/30/the-agricultural-mind/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2020/12/13/the-drugged-up-birth-of-modernity/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/06/30/yes-tea-banished-the-fairies/

The argument from Henrich, Steven Heine and Ara Norenzayan that people in the WEIRD demo graphic are behavioral ‘outliers’ is open to dispute.

On what basis is the outlier status calculated? If by population size, then yes.

But if by GDP, then according to IMF 2009 statistics of millions of GDP:

World 57,843,376

European Union 16,414,697

United States 14,119,050

therefore the EU and USA account for 52.8% of world GDP alone. On this basis, they are not WEIRD at all, but the majority.

If one does the analysis by population numbers, of course, the result is not the same.

However, since the inevitable trend seems to be for more education, industrialisation and democracy (if not richness), then the WEIRD societies seem to indicate the trend that all the world is headed for, and therefore, in reality, an excellent source of experimental data if one is concerned with the future state of the world.

So, I would suggest you think up another name – perhaps WIRED – Western Industrialised Rich Educated Democracies. This is much more in tune with the whole way everything is going, and as a bonus, does not reek of the defeatist left-liberal mind-set that created WEIRD.

In addition, I would add that the invention of nonsense like WEIRD is exactly why psychologists have such a bad name with the general public.

That’s all well and good, but the goal of psychological research is often to identify innate tendencies and functions of the human mind/psyche. If, and it seems this is indeed the case, other cultures vary tremendously from ours in these areas it means that behavior patters or other traits that we originally thought were innate are not, which is important information for any field that claims to be discovering innate tendencies.

It is also bizarre to try to argue that we should consider westerners as being more normal simply because they are more wealthy. What sort of logic is that? How arbitrary.

There is nothing defeatist in noting that among human beings as a whole, westerners comprise a minority and at times display atypical behavior. It is not a value judgment.

Henrich argues that two main factors that contributed to the WEIRD phenomenon is mass literacy and nuclear families. But maybe those factors didn’t make for a catchy acronym.

Great discussion. My only quibble is the suggestion that the WEIRD and the ‘small scale’ might overlap in the rather favorable set up described. It is the total infrastructure that matters. Health facilities, manufactured goods, educational, law enforcement etc – growing a few veggies is a mere biofilm on the basic machinery. Just the concept of a land title for example can make a real difference – probably something we all take for granted. (if we’re weird of course)

I thought the ideas about physical differences very telling – activities of the body must affect psychology. Have a look at ‘Haiti Under Construction’ in youtube – first instinct might be to laugh, next to groan or deride for ignorance but eventually you may come to admire.

You are correct that, “Just the concept of a land title for example can make a real difference.” The Jaynesian scholar Brian J. McVeigh has theorized about the propertied self. It relates to the literate, literary, and typographic self. Land deeds, after all, are written texts.

But I’d also argue it relates to the legible self, as described by James C. Scott in his book Seeing Like a State. And like Scott, I suspect it’s related to agriculture, specifically grain farming, especially in the West as opposed to Eastern grain farming (Thomas Talhelm).

It’s not only about what we farm but also how what we farm determines how we use land. And then how we use land shaping identity. Some early modern land reformers, such as William Godwin, understood and openly stated that his real goal was moral reform and identity reform.

That is, you can’t strategically retreat to abstract high ground as soon as you’re challenged empirically on sloppy universalisms only to boldly foray forth into the land of blanket statements about more detailed characteristics of ‘human nature’ as soon as you think no one is watching.

What I don’t get, I guess, is the defensiveness. Are the knee-jerk universalists worried that, if we concede that there might be fundamental variation in humans, we inevitably move toward racism? If so, we’re in trouble. Do they think that the existence of human genes means that we must necessarily be a species of genetic clones?

I totally agree that we’re not a clonal species, but I still think that it’s more parsimonious not to assume that non-universals are rooted in genetic determination. Speaking of “universals” and lack thereof, culture probably is the most/only constant universal, and also the key factor for everything that is not.

Whenever genetic determinism/strong enough influence seems to really be the case, the odds just happen to be that it wouldn’t so much of a racial thing, as most of human genetic variation is shared by all races. It could still be the case that sometimes there would be non-universals that are considerably genetically based and such genes are found in significantly differing frequencies along the races, though. But I think that the odds would be that it’s quite rare, possibly something that “does not even occur”, or that is dwarfed by the role of shared genes that are more evenly distributed, and sheer non-genetic determination.

I have this suspicion/gut feeling that perhaps the most significant form of “genetic determinism” in racial/group differences would be something like the cultural adoption of “behaviors” that are genetically influenced in some individuals, who happened to be more “culturally influential” for whatever reason. Not necessarily at an “individual” level anyway, they don’t need to be “celebrities” of any kind, nor the first ones who copy their behavior. It is not rigidly dependent of the allelic frequencies. It could happen that the cultural influence outlives the meaningful frequencies of the influential alleles. Or even that the cultural influence grows throughout the population regardless of the negligible frequency of the influential genetic variation, that may be rare from the start.

Cool infographic out now on Henrich’s findings: http://www.bestpsychologydegrees.org/american-psychology/

I think this paper and discussion is also critically important for philosophers, especially critical theory/cultural studies folks. They have a tradition many centuries old of examining their own personal thoughts and thought processes and making claims about human nature based on them.

A few other thoughts I hope are worth mentioning: a huge percentage of university students, especially psychology students would be my expectation, are taking various prescribed medications often of the mental health variety. They have meds for their ADD/ADHD, their depression, their anxiety, their bipolar disorder, etc. Then there are the drugs for the aches and pains so frequent in the incredibly inactive, drugs to deal with the stomach pains of a toxic diet, the list is long. A great number drink large amounts of alcohol and then we get to the illegal narcotic substances which are also widely used. Topping off this list are various artificial ingredients in foods that are known to effect the mind. Even our gut biota is quite different from that of a non-WEIRD person, and that can effect behavior as well. Finally, we may well be exposed to different pathogens and there is at least one pathogen, transmitted by cats, which there is good reason to suspect alters our behavior.

It would be interesting to see if one were to use a WEIRD population that intentionally excluded those using various medical or illegal drugs whether that alone would make them more “normal.”

About Western philosophy, the related field of philology used to be popular. It often covered similar territory of philosophy, but had a particular focus on cultural study, linguistic, and textual analysis. Many of those philologists, as with the cultural anthropologists, basically made an argument for WEIRD bias long ago.

The other part of your comment is particularly important. And it has been largely neglected, if simply for lack of knowledge and familiarity. Most social scientists, biologists, nutritionists, etc never interact within academia and research. But you are correct these physiological factors can have powerful affect on psyche, behavior, and culture.

There is a ton of research out there on how various external factors. Individual parasites such as toxoplasma gondii alter the brain in ways that can be measured in personality traits and behavioral outcomes, but it is also correlated to population-wide patterns. Overall parasite load increases authoritarianism and conservatism in populations. There are plenty of studies on diet and microbiome, as well.

I’ve written about this. Some of it is grounded in scientific evidence, but much of it is speculative. For example, we know that the Nazi leadership, military, and general population had high rates of methamphetamine addiction. And we scientifically know how meth use changes physiology such as hormone levels and changes cognition, perception, and behavior. But one has to extrapolate from this evidence what it means for an entire society.

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2020/12/13/the-drugged-up-birth-of-modernity/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/06/13/diets-and-systems/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/01/30/the-agricultural-mind/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/06/30/yes-tea-banished-the-fairies/

https://benjamindavidsteele.wordpress.com/2019/07/25/autism-and-the-upper-crust/

I wonder if modern studies using WEIRD students exclude the ones using drugs that affect the mind? I would expect the vast majority of psychology undergrads to be on some meds for ADD/ADHD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and/or to be taking or have taken illegal drugs. One hit of LSD for example can permanently alter some behaviors and views. If they do not exclude these students then they are surely not revealing human nature.

Other similar but less obvious confounds could be drugs not for mental health that still have some mental effect, infection with parasites (http://www.livescience.com/933-study-cat-parasite-affects-human-culture.html), and eating artificial chemicals that affect mental functioning or even just large amounts of sugar.

So it seems unclear whether the students themselves are WEIRD or whether all of the above dramatically alters results in these studies.

The thing is it’s not only WEIRDos who use drugs. Rather, what has changed in the modern West is the kinds of drugs used. The addictive drugs, particularly stimulants (caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, etc), have become more commonly used; whereas some argue psychedelic use has declined over the centuries.

It’s not only that tea and coffee (later, caffeinated pop and energy drinks) replaced beer as an everyday drink in the West. The traditional beers made in past centuries often included mildly psychotropic herbs. Also, old European pictures sometimes portrayed psilocybin mushrooms, indicating their use was part of cultural practice.

There are few places on earth where there wasn’t traditional access to psychedelics, particularly among hunter-gatherers. So, simply trying to control this confounder by only using non-drug users would end up introducing yet another WEIRD bias. To get away from the WEIRD bias, researchers might have to introduce more users of plant psychedelics.

I have a linguistics background, though I am not a card-carrying professional linguist. Over the last few decades people with an interest in language universals are beginning to converge after a long period of divergence. There are very few universal universals in language: Hauser, Fitch, and Chomsky 2002 actually reduce the number to one.

But there are a large and growing number of statistical universals, conditional universals (“If X is present in a language, then Y is present too”) and indeed statistical conditional universals, all of which need explanation. The alternative (meta-)explanation is in terms of parameters, in which conditional universals are explained by an underlying psychological parameter that is either ON or OFF for each language, and a child simply has to learn which parameters are ON. This approach has run into massive difficulties: there is no agreement on a universal list of parameters, and the number of parameters tends to grow as more papers are written until it approaches one parameter per universal, which undermines the whole idea.

Many of the known universals can be accounted for on functional grounds. If you put the subject and the object on the same side of the verb, you need some way to reliably distinguish them such as case endings or particles like the Spanish “personal a“. But there is a residue that don’t seem to be functional, and they can’t be just brute-force accidents like the English word for ‘snow’ being snow, for which the explanation is entirely historical: as the biologists say, it is that way because it got that way. For example, why is it that if a language has case-marking on inanimate nouns, it also case-marks animate nouns, whereas if it lacks case-marking on inanimate nouns, it may mark either all animate nouns or just human nouns? We doesn’t know and (unlike Gollum) we very much wants to know.

Americans are very homogeneous

It’s all in the point of view. Israelis, I am told, see people from the U.S, the U.K., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, … as all interchangeable “Anglo-Saxons”. On the other hand, as a New York City resident for 40 years (though not born in the city and fairly WEIRD myself), “Americans” look very diverse to me. Almost 40% of New Yorkers are foreign-born, for example, though half of those are non-citizens. Even our public universities have a lot of non-WEIRDos. (I prefer this term to “WEIRD people”).

You write that, “There are very few universal universals in language: Hauser, Fitch, and Chomsky 2002 actually reduce the number to one.” Then again, some reduce it even further to zero. It has been argued that linguistic cultures do exist that lack linguistic recursion. It’s a common trait, bug not necessarily universal.

Where a universal is obvious is simply in the fact that all known human societies have language. A language instinct does seem to be built into human nature. And that language instinct does conform to general patterns of language (words, phrases, etc), if the potential there is great diversity in the expression.

If one wants a challenge, try to make an acronym out of all the following. When one starts thinking about modern Western middle class white Americans and other Westerners, the factors and conditions that differentiate and distinguish them are so numerous as to be near endless, forming a complex web where none alone can explain what is going on. Part of the problem is many researchers like Henrich, Heine, and Ara Norenzayan, no matter how widely they attempt to cast their net, may still fall into the typical trap of the academic silo. There are other fields of research that could shed some light, specifically related to how we use language and how language shapes us, along with what relates to language. I’m thinking of philology, linguistic relativity, media studies, and consciousness studies: Marshall McLuhan, Walter J. Ong, Eric Havelock, E. R. Dodds, Bruno Snell, Julian Jaynes, Edward Sapir, Benjamin Lee Whorf, etc. Silent reading and hence presumably an inner voice, for example, was only widely common after the spread of punctuation in the Middle Ages. And or course, the moveable type printing press transformed all of modern civilization, not just technologically, economically, and politically but also culturally, socially, and psychologically.