Ah, rafting the San Juan River in southern Utah, camping and hiking for a week – for most people, a vacation. But for a select group of brain researchers, and some accompanying journalists, it was “serious work.”

Ah, rafting the San Juan River in southern Utah, camping and hiking for a week – for most people, a vacation. But for a select group of brain researchers, and some accompanying journalists, it was “serious work.”

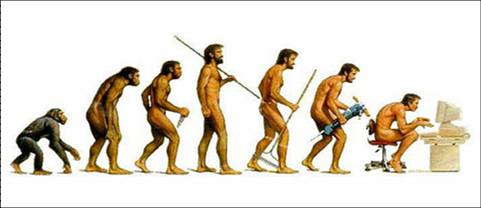

It was a primitive trip with a sophisticated goal: to understand how heavy use of digital devices and other technology changes how we think and behave, and how a retreat into nature might reverse those effects.

The whole technology vs. nature theme is a hit, as the NY Times article, Your Brain on Computers: Outdoors and Out of Reach, Studying the Brain, is the most popular article there right now. But that dichotomy of technology as bad and nature as good is a false one. Worse, the prism of the brain proves to be dangerous rapids rather than a river of explanation.

I’ll start with the money quote for me:

Back in the car, Mr. Kramer says he checked his phone because he was waiting for important news: whether his lab has received a $25 million grant from the military to apply neuroscience to the study of ergonomics. He has instructed his staff to send a text message to an emergency satellite phone the group will carry with them.

Mr. Atchley says he doesn’t understand why Mr. Kramer would bother. “The grant will still be there when you get back,” he says.

“Of course you’d want to know about a $25 million grant,” Mr. Kramer responds. Pressed by Mr. Atchley on the significance of knowing immediately, he adds: “They would expect me to get right back to them.”

It is a debate that has become increasingly common as technology has redefined the notion of what is “urgent.” How soon do people need to get information and respond to it? The believers in the group say the drumbeat of incoming data has created a false sense of urgency that can affect people’s ability to focus.

The anthropologists among you should already know where I am going – the conflation of a social expectation, a social reality, with a technological cause. The money quote really is just this, “They would expect me to get right back to them.” But rather than dwelling on that, the piece then asserts that “technology has redefined the notion of what is ‘urgent’.” Sorry, but it was actually people who did that, people and their social expectations. Technology doesn’t come to us unmediated by culture. Rather, technology is culture.

Unfortunately a good ethnographic moment, which says one thing about human life, is turned into a reductive, brain-oriented explanation in the next paragraph – the expectation to get back to someone becomes the drumbeat of incoming data. Yet they are two very different things.

Continue reading “Your Brain Unleashed – Outdoors and Out of Reach”