Making the rounds of neuro-related sites on the web is a recent story from Wired, Brain Scanners Can See Your Decisions Before You Make Them, by Brandon Keim. It’s an interesting short piece on an even more interesting research paper by Chun Siong Soon, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes forthcoming in Nature Neuroscience (abstract here). But like so much in the science writing about neurosciences, the piece leaves me feeling like either I don’t get it or science writers really don’t understand the significance of basic brain research. I won’t dwell too much on my issues though with the science writer because I want to really consider the relationship between brain activity and experience, or what role phenomenology might serve in neuroanthropology (besides, I’ve been railing at science writers a bit too much of late…).

Making the rounds of neuro-related sites on the web is a recent story from Wired, Brain Scanners Can See Your Decisions Before You Make Them, by Brandon Keim. It’s an interesting short piece on an even more interesting research paper by Chun Siong Soon, Marcel Brass, Hans-Jochen Heinze and John-Dylan Haynes forthcoming in Nature Neuroscience (abstract here). But like so much in the science writing about neurosciences, the piece leaves me feeling like either I don’t get it or science writers really don’t understand the significance of basic brain research. I won’t dwell too much on my issues though with the science writer because I want to really consider the relationship between brain activity and experience, or what role phenomenology might serve in neuroanthropology (besides, I’ve been railing at science writers a bit too much of late…).

From Keim’s article, we have this explanation of Haynes’ work:

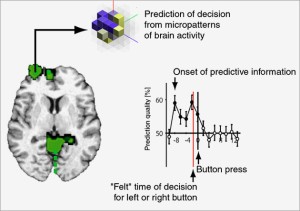

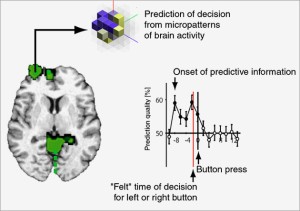

Haynes updated a classic experiment by the late Benjamin Libet, who showed that a brain region involved in coordinating motor activity fired a fraction of a second before test subjects chose to push a button. Later studies supported Libet’s theory that subconscious activity preceded and determined conscious choice [I have a problem with that phrase, especially ‘determined’] — but none found such a vast gap between a decision and the experience of making it as Haynes’ study has….

Taken together, the patterns [in frontopolar cortex and then parietal cortex] consistently predicted whether test subjects eventually pushed a button with their left or right hand — a choice that, to them, felt like the outcome of conscious deliberation. For those accustomed to thinking of themselves as having free will, the implications are far more unsettling than learning about the physiological basis of other brain functions.

The Libet research is a classic piece (I don’t know if it makes any top 100 lists, but it’s especially important to those of us interested in motor action). The problem seems to be forcing Haynes’ data — which confirms Libet’s older research about the subconscious activity that precedes conscious awareness of ‘choice’ — through a folk theory about ‘free will’ being a necessarily conscious activity setting in motion a chain of mind events leading up to action. Folk understandings posit the existence of ‘The Decider’ in the brain, a kind of uncaused cause, the prime neural mover, which is conscious.

Bottom line, as far as I’m concerned: the research can’t be proving whether or not we have ‘free will’ because ‘free will’ is fundamentally about constraints on ‘will’ (itself a fuzzy concept when you’re looking at brain imaging). That is, the research would have to examine not what the brain does when it makes a choice, but whether that brain activity was constrained by something external to the person. After all, if we say that a person’s ‘free will’ is limited by their brain, that doesn’t really make sense now, does it? Presumably, acts of a ‘free will’ would also be determined by the brain, wouldn’t they? For the brain to ‘constrain’ our own ‘free will,’ it would have to be a thing separate from us.

What the research is showing, however, is something fascinating about the relationship of phenomenology and native categories of mind and how they might intersect with brain science research.

Continue reading “How well do we know our brains?”