Paul Mason has sent me PowerPoint slides on Neuroanthropology that draw upon a lot of the same resources that he cited in an earlier post I put up on his behalf. Paul’s in the field in Indonesia, and he writes in sometimes from internet cafes, but we should eventually have him as a regular contributor when he’s back with some regular Internet access. And then he can also tell us more, too, about his own research.

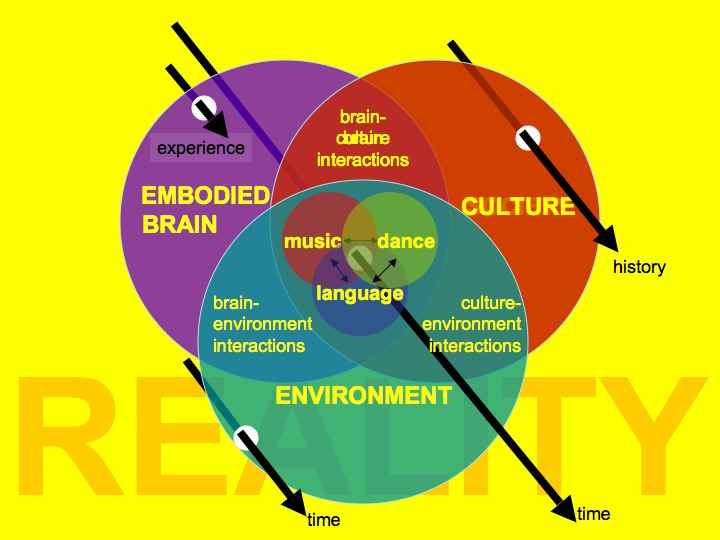

Paul includes a number of choice quotes, but I wanted to make sure that everyone got a chance to see his diagram of a systems-based approach to ‘fight-dancing’ in cultural, biological, and ecological context (in both Indonesia and Brazil). It’s a rich diagram, and I think that we, as neuroanthropologist, will need to do a lot of complex visualization in order to make our points to a broad audience. Paul must get all the credit for this one. In the meantime, i don’t yet have a complete bibliography on this material, so we’ll have to get in touch with Paul if anyone really wants to get the sources he’s using. He sent this about a month ago, and I was not clear on how to post PowerPoint slides, but I think it’s pretty straightforward. We’ll see….neuroanthropology.ppt

In the meantime, i don’t yet have a complete bibliography on this material, so we’ll have to get in touch with Paul if anyone really wants to get the sources he’s using. He sent this about a month ago, and I was not clear on how to post PowerPoint slides, but I think it’s pretty straightforward. We’ll see….neuroanthropology.ppt