Language diversity around the world is decreasing and Razib Khan of the Discover science blog, Gene Expression, doesn’t think you should care. I was going to let it slide because I don’t like getting in little blog tiffs, but then Khan went and tried to co-opt Neuroanthropology.net into the whole thing, so he forced my hand.

I had started to do a quick survey of the obvious, easily Googled data that might support or refute Khan’s argument, but decided that it was petty to point out the glaring logical, empirical and philosophical problems with his arguments, so I was just going to let it go. But then Khan took the liberty of demeaning my discipline and even linked through to my own site to supposedly support his argument, so I’m going to take the liberty of blogging while angry, which is kind of like drunk texting only more time consuming. I’m not really worried that Khan will actually read this post carefully, however, as he apparently didn’t bother to read closely the post to which he actually linked.

Khan doesn’t think linguistic diversity matters. After all, language diversity correlates with poverty, he argues. The evidence he produces for this is a graph that is apparently more of a thought experiment than any sort of actual data plot. So I thought I might just explore this question with a little anecdotal data like comparisons between nominal GDP/capita and numbers of indigenous languages in Ethnologue and how well these seem to correlate. I’m neither a statistician nor do I want to devote more time to this, but I want to just present some evidence in the discussion (especially because he implies anthropology is a kind of salon game for the intelligentsia and for fact-challenged jargon heads).

Normally, I try to be a pretty positive online presence, not prone to hurling invective or belittling other writers, but there are a few things that get me really hacked off, and one of them is conservative Social Darwinism thinly veiled with pseudo-science, as if this is just ‘nature’s’ way of sorting out the winners from the losers. Razib Khan’s example makes me particularly angry because he links in the direction of Neuroanthropology.net like something we argue supports this (please take down the link, Khan, if you read it – we don’t need your traffic if it comes from people who think we’re in your corner). Moreover, Khan’s argument demonstrates an extraordinary callousness, suggesting that concern about language rights assured in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other UN human rights documents are just a kind of bourgie latté sippers’ hysteria that people concerned about the ‘real world’ don’t share.

Linguistic diversity? Liberal conspiracy

Khan thinks all the concern about language preservation is an elitist projection:

The moral panic that many Westerners have over the extinction of small-scale societies is not shared by many members of those small-scale societies, who wish to opt-out, often for material reasons. And by material, I’m not talking McMansions, I’m talking having income above subsistence. The level of wealth of a Chinese factory worker, not that of an academic adjunct. (emphasis in the original)

On what does he base this statement? He’s smelled Dhaka, and it ‘smells like human shit. That’s poverty.’ Yeah, stinking poverty caused by their languages!

Everyone is ditching their local languages because they are abjectly poor and they realize that their ‘little’ languages are keeping them that way, so they wisely decide – oh, I’m sorry – make ‘rational decisions in a world of constrained choices’ (emphasis in the original): they want to get on that big global language bus to a solid paycheck and three square meals a day! And their choices are constrained, cause they’re poor! Stinking poor!

I’m going to try not to be petty (it’s hard), but I think Khan’s post is extraordinarily callous, far outside his area of expertise (which is apparently blogging… sorry, that was petty), and a bit of ideology parading as science (a problem which he ascribes to his critics). When confronted with criticism on the first post, Khan refuses to reflect or consider other options, but just doubles down on his original off-handed remarks (here and here), elaborating them into two more posts on why we shouldn’t care about Indigenous languages, often with divergent and even contradictory rationales, and then insulting my discipline. I hereby accept the gauntlet, pitiable knave!

Diversity and resilience: the initial stimulus

The series of posts started with Khan’s response to Seed Magazine republishing a 2008 piece by Maywa Montenegro and Terry Glavin, ‘In Defense of Difference.’ In the piece, Montenegro and Glavin highlight the convergence of thinking about both decreasing biological diversity and cultural diversity. Although the situation for global ecosystems is more widely known among scientists, in fact, the risks for the world’s linguistic diversity are equally dire. As Montenegro and Glavin decribe, ‘Of the world’s roughly 6,800 languages, fully half — though some experts say closer to 90 percent — are expected to disappear before the end of the century.’ The piece begins with the description of the funeral for Marie Smith Jones, the last fluent speaker of Eyak in Anchorage, citing a number of examples of ‘a global epidemic of sameness’: ‘this epidemic carries away an entire human language every two weeks, destroys a domesticated food-crop variety every six hours, and kills off an entire species every few minutes.’

Montenegro and Glavin discuss how concerns about decreasing biological, ecological and cultural diversity have merged in studies of system ‘resilience,’ or the role of diversity in the continuing function of complex systems in changing conditions. We know well that some biological systems need diversity; for example, I doubt very much that Khan and other sceptics of language diversity would be quite so blasé if we were discussing decreasing diversity in the antibodies produced by the immune system. Although I’m not fully persuaded by Montenegro and Glavin’s arguments (and others’) that biodiversity and cultural and linguistic diversity are linked, the occurrence of biodiversity and cultural diversity in the same areas is intriguing.

The danger is not simply that there’s too little diversity, it’s that we don’t even have a handle on the diversity that’s disappearing. Montenegro and Glavin:

While no reliable data concerning the level of documentation of the world’s languages exists, a plausible estimate is that fewer than 10 percent are “well documented,” meaning that they have comprehensive grammars, extensive dictionaries, and abundant texts in a variety of genres and media. The remaining 90 percent are, to varying degrees, underdocumented, or, for all intents and purposes, not documented at all.

The problem in language diversity is that the vast majority of languages are spoken by a tiny minority of the world’s population. As Montenegro and Glavin explain: ‘more than 96 percent of the world’s languages are spoken by just 4 percent of its people.’

Now I have to admit, I’m not entirely persuaded that language diversity does increase human resilience, although I do think cultural diversity in general does increase innovation. The resilience argument is not one that I would use to advocate preservation of Indigenous languages, but I’ll get back to that in a minute…

Razib Khan thinks it’s no big thang

Khan starts off his series of statements against those who worry about decreasing language diversity in a brief discussion of various web links, including the piece by Montenegro and Glavin. He was of the opinion: ‘If Eyak language was so awesome, why wasn’t the article written in Eyak? I find the paeans to linguistic and cultural diversity tiresome and knee-jerk.’ He then goes on to confuse the case completely, arguing that ‘diversity’ is actually bad sometimes because in the nineteenth century, people had ‘diverse’ views about slavery, but now we’re better because we’re universally against slavery. QED, diversity is weak. (Fortunately, in the two posts that follow, he doesn’t continue along this rather tendentious argument by straining analogy.)

In the second post, departing in the opposite direction, Khan explains with a not-entirely-persuasive mathematical analogy, saying that hybrids of cultures actually increases overall cultural diversity (his example is ‘half-Chinese & half-English devotees of Vaishnava Hinduism’): ‘There are more combinations as the fuller possible parameter space is being explored, despite the decrease in the number of modes across the distributions.’ Okay, let me see if I get this: cultural diversity is not of value, so don’t care about it decreasing, but, by the way, cultural diversity is actually increasing because although the number of cultures (wasn’t this about languages?) is decreasing, there are more hybrids. (Remember this as one example of Khan’s off-handed use of academic jargon to dress up his ideas – we’ll get back to this.)

Apparently, Khan felt a bit of heat for his dismissal of concerns about decreasing linguistic diversity, but, rather than rethinking his position, he just ups the ante and draws some analogies to Stanley Diamond to shore up his ‘never-mind-the-cultural-diversity-it’s-all-good’ argument (by the way, in post #3, he decides to off-handedly diss Stanley Diamond, possibly to throw his critics off, since he said he was simply paraphrasing or extending Diamond’s argument in piece #2). The good news is that he includes a much more open discussion of the value of language for identity, distinctive worldviews, even literature, suggesting that ‘Language is history and memory.’ He even waxes eloquently about how linguist nuance gives ‘intangible aesthetic coloring to the world’ – wow.

But he still doesn’t care about language extinction.

The key for Khan is that he thinks the preservation of linguistic diversity is an imposition on those individuals in minority communities:

But this [advocacy of language diversity] ignores the costs to those who do not speak world languages with a high level of fluency. The cost of collective color and diversity may be their individual poverty (i.e., we who speak world languages gain, but incur no costs).

Khan puts forward the argument assuming that 1) you must not be able to speak a world language without sacrificing your native language, 2) language preservation is foisted upon minority linguistic communities by rich people for their own gratification, 3) language diversity causes you to be poor or at least prevents you from getting rich, and 4) rich people don’t learn ‘little’ languages (a particularly interesting assumption considering the dismissive things he has to say about the field of anthropology, where we do this kind of thing).

He says of a couple of critics, ‘if anthro-gibberish drives you crazy, don’t follow the links.’ Okay: one catty remark: at least the anthropologists know what the word ‘vacuous’ means, especially handy if you want to keep using it.

He says of a couple of critics, ‘if anthro-gibberish drives you crazy, don’t follow the links.’ Okay: one catty remark: at least the anthropologists know what the word ‘vacuous’ means, especially handy if you want to keep using it.

The problem with his critics is that they just get all tied up in their semantic intellectual games and don’t understand the core truths:

Many anthropological types problematize too much for my taste. They confuse the nuance and shading which vary between societies, for the core truths, which are relatively culture-free. For almost all of human history most people lived at the poverty line, because Malthusian conditions were operative. The possibility for wealth, and consumer society, is new. Those who opt-out in modern societies do so for explicit ideological reasons and are aware of the trade offs (e.g., the Amish, Hasidic Jews, people who live in communes).

Of course, if Khan had gotten over his aversion to ‘anthropological types’ with our incessant problematizing, he might have learned along the way about the correlation between the industrial revolution and advanced farming techniques and increasing rates of populations growth. Khan might have learned how surprisingly stable some indigenous populations have been over time (and cases where that had not been the case, often with ecological disaster quickly following). If Khan were actually reading anthropology, or even history, he might learn the role of enclosure in destabilizing rural populations to make them ‘poor,’ or the troubles colonial officials had talking subsistence farmers into producing cash crops because they correctly perceived that they would suddenly become ‘poor’ when they no longer were self-sufficient.

If Khan had read one of the classic works of anthropology in the last century, Stone Age Economics, by Prof. Marshall Sahlins, he might not so flippantly declare: ‘For almost all of human history most people lived at the poverty line…’ a statement that simultaneously commits at least three fundamental errors in only thirteen words. Heck, even a cursory reading of John Kenneth Galbraith might have made him less reckless, but I digress…

Also, Khan assumes that those who ‘opt-out’ in ‘modern societies’ (again, more errors than I care to correct) do so voluntarily, apparently passing over the people who are ‘opted-out’ because they’re just poor. And there’s no consideration that wealth in some countries might actually be related, somehow, remotely, to poverty in others. Books have been written about the fundamental Modernist errors that Khan glides through: that poverty is because people are traditionalists (some of the poorest are those who are integrated into the global economy tightly but in horrible conditions or moved to satellite manufacturing areas in periphery countries), that there is no poverty in the developed world (except those who ‘opt-out’), that everyone, everywhere, before the advent of capitalism, was ‘poor.’ God, I’d like to get this kid in my economic anthropology class…

Razib Khan has this to offer to those who actually study culture, human diversity, language, and the like, in closing:

For a better understanding of how I approach anthropology, and the study of human culture, the first half of D. Jason Slone’s Theological Incorrectness describes it almost perfectly. If you continue to read this weblog, you’ll note that I have a deep interest in culture and history. But, my treatment is not going to resemble much of what would find in cultural anthropology in the United States. In fact, I’ll drive you crazy, and perhaps an r-squared here and there will strike as you positivist gibberish. No one’s paying you to read though.

I don’t think an ‘r-squared here and there’ is ‘positivist gibberish.’ I think that pulling stuff out of your a** as you go, making up facts, conveniently rereading or simply being ignorant of history, trying to hide it with shallow engagement with economic terminolgy or statistics, and misusing academic concepts is just gibberish. Unqualified. Not ‘positivist.’

But rather than just hurl invective at an individual who has just dismissed my academic field, I’d like to talk about, well, some evidence. Fortunately, since I hail from anthropology, I can be contented with a bit of anecdotal sampling and a few back-of-the-envelope scribblings to see how the Khan Theorem of Linguistic Diversity = Poverty holds up to, well, empirical reality. So, in a non-systematic and purely on-line-from-my-relatives’-home kind of way, let’s look at some rich countries and some poor countries…

The evidence

Khan doesn’t really have any data, but he does offer a graph that’s a kind of thought experiment based upon his idea of how the world works. His graph, which I won’t reproduce here out of respect for his intellectual rights, suggests that, with everyone speaking their own language, ‘median human utility’ would be zero. As language use become more and more homogenized – two people speak each language, then three – eventually, median human utility would reach a plateau. But then, at a certain point beyond the maximal language ‘oligopoly’ (his term), median human utility would then drop again.

Of course, those who advocate for language diversity do not suggest that everyone should have their own private language, nor are they engaged in thought experiments. They are actually struggling for the language rights of minority groups around the world who exist in a form other than on a hypothetical graph. So instead of testing the thesis with hypothetical extremes – one person-one language and global monolanguage – let’s look at actual countries with different (or a single) language.

As a caveat to this, quantitative analysis of this sort is not a personal strength, and I’m usually the one talking about ‘lies, damn lies, and statistics,’ but the comparisons at least, even stripped of the pseudo-analysis, are worth considering.

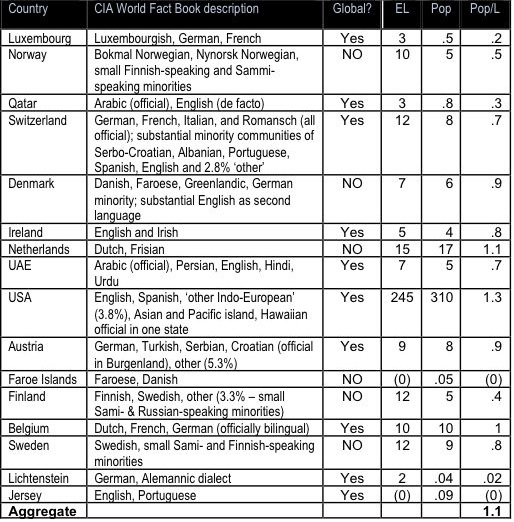

We could start with the countries with the highest nominal gross domestic product per capita (admittedly, a rough measurement of ‘utility’ but easier to get than something like human development index or an agreed-upon measure of national ‘happiness’). Luxembourg, Norway, Qatar, Switzerland, Denmark, Ireland, Netherlands, UAE, USA and Austria were the top ten per capita GDP countries according to the IMF as of 2009. Just to increase our pool, I’ll also pull other top-10 earners according to the CIA Factbook and the World Bank: these would include Finland, Sweden, Belgium, Lichtenstein, the Faroe Islands and Jersey. So are all these countries monolingual speakers of world languages?

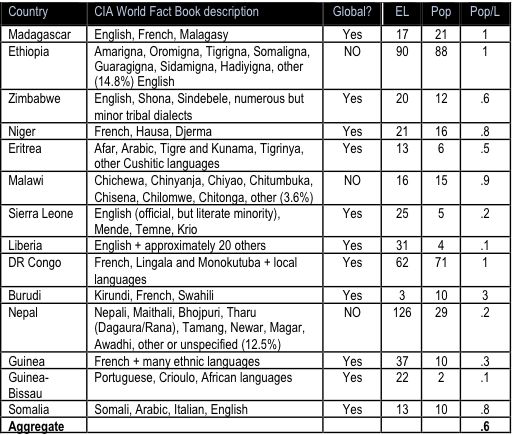

The following table lists 16 of the wealthiest countries in the world, the CIA World Fact Book description of their current language scene as well as some key facts: the first (‘Global?’) describes whether one of their official languages is a ‘Global’ language spoken by 50 million people or more. ‘EL’ is the number of non-immigrant languages (that is, native languages) spoken in a country according to Ethnologue; ‘Pop’ is the population of the country in millions; and ‘Pop/L’ is the total population in millions divided by the number of languages, a very approximate (very, very approximate) sign of language diversity. The higher the ‘Pop/L’ score, very roughly, the less the linguistic diversity in a country.

The very last line on the table is an aggregate Pop/L, the total population of the wealthiest countries in terms of nominal GDP/capita divided by the total languages; I didn’t bother to remove duplicates and I pulled out the Faroe Islands and Jersey (they don’t really have ‘0’ population) because I don’t have complete information to do my back-of-the-napkin comparisons. Besides, they’d likely artificially lower Pop/L as they have such small populations (and speak duplicate languages found in other rich countries).

Of course, Pop/L, being a back-of-the-napkin calculation, is sloppy, getting worse the larger a country’s population is, as a large number of very small language communities can lower a Pop/L without signifying that a population is really all that linguistically diverse. But the same problem occurs with nominal gross domestic product per capita, so I’m going to run with it. If you really wanted to measure linguistic diversity, you’d have to come up with something analogous to the Gini coefficient, the measure of inequalities in wealth; if it’s out there, someone will tell us, I hope. That said, here’s the table:

How about the correlation of linguistic diversity with poverty? The ten poorest countries, according to the IMF, are all African: Madagascar, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Niger, Eritrea, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Liberia, DR Congo, and Burudi. Adding in my two other sources would increase the pool with Nepal (the only non-African country), Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, and Somalia.

The analysis, of the admittedly anecdotal data, that is…

So what’s this all suggest? First, that a higher proportion of the poorest countries have ‘global’ languages (for the sake of argument, those with more than 50 million speakers) among their official languages than among the wealthiest countries. I’m sure Khan, like me, is skeptical of the possible gap between ‘official’ language and actual language spoken, but the gap would only exaggerate the importance of that global language relative to the local language that was not official. If business, government, legislation, tertiary education, and a host of other opportunities and resources in a country depend upon learning a language that you do not speak, then you theoretically would have more motivation to learn that language (if, in fact, one was motivated to learn language by ‘rational decisions in a world of constrained choices’ – by the way, is ‘economese’ a global language yet? 50 million speakers?).

But certainly we can say that the governments of poor countries are doing their part to end poverty by making global languages official, right? The much easier explanation of the pattern is that, if you were colonized by a global power, you stand a much greater chance of having a global language installed as your official language (of course, the irony is that so many wealthy countries seem not to have gotten all their languages to become ‘global’ nor have they spent time, money and energy eradicating these pesky little local languages that they have in their borders).

Okay, so making a global language your official language as panacea to national poverty? Not so compelling a case here.

How about language diversity undermining national prosperity, certainly this bears out in the data, right? The total aggregate ‘Pop/L,’ our admittedly messy surrogate for language diversity, in the whole globe is around 1(Population of the world (6.9 billion or 6900 million)/Total number of language (6909) = 1). Here, we might have something: the rich are more linguistically homogeneous! Their aggregate Pop/L is 1.1, which everyone knows is more than 1! And the Pop/L of the poor countries is .6, which is a lot lower than 1.

Of course, things are not quite so clear as this (Khan doesn’t like the way that anthropologist ‘problematize’ but we can’t help ourselves). If we look at the rich countries, one of them stands out like a sore thumb: the US. On virtually every measure, the US is out of place. Identified as a ‘linguistic hotspot’ by people who concern themselves with these things, with a population so large that it skews the pattern of all the other states. Arguably, the high EL is actually a distortion, as the significant populations of non-English speakers might be much smaller (with Spanish and a few others, perhaps, if the analyst was feeling generous). What about the other countries? Without the US, the Pop/L of the remaining wealthiest countries would be .7. The huge US population, even with the very large number of languages, helps to pull up the aggregate average.

In addition, there’s one of the six linguistic hotspots among the poorest countries as well: Nepal, the only non-African country. If you pull the two linguistic hotspots out of the data – the US and Nepal – the pattern among the rest is surprisingly similar. The Pop/L of the rich is .733 and of the poor, .730 (the extra decimal places added to impress those who have extra strong faith in numbers). Since our method likely inflates aggregate Pop/L relative to global Pop/L (because we don’t eliminate duplicates in aggregate, but they’re eliminated in global numbers), I think we really wind up with one thing to conclude about the ‘Language Diversity Causes Poverty’ Hypothesis: meh.

I say, ‘meh,’ and not, ‘no,’ because it may or may not be the case, but it seems to me that other factors are obviously more likely explanations. After all, other patterns are far more obvious: like being African, or politically stable, or formerly colonized, having corrupt government or an especially damaging war, or being European (even Scandinavian)… Certainly, I don’t think most people would look at these charts and say, ‘My God man, we must save these poor countries from their linguistic diversity and make them like the linguistically homogeneous rich countries!’

On average, the wealthiest and the poorest countries are not enormously different to the global average; like I said, we’d need a measure of language concentration to really be able to judge this. At the very least, the data suggests that there’s not really much of an upside to increasing homogeneity beyond the average – the wealthiest countries don’t seem to be exceptionally homogeneous (except for that outlier, you might argue).

Moreover, the rich group is hardly characterized by the use of global languages as first tongues in spite of the fact that they come from a region where languages have disproportionately become global languages through conquest. In contrast, no native African language has more than 50 million native speakers, unless you include Arabic. Plenty of very wealthy small European countries have boutique national languages and support indigenous language groups; in my experience, many American writers tend to dismiss the example of well-to-do Scandinavian and Western European countries when rhetorically convenient, like on the subject of socialism, the pernicious effect of high taxes, or linguistic diversity. A number of the high performing countries have primary languages that are not global and many support substantial Indigenous populations that preserve linguistic distinctiveness.

I would go so far as to say that the data suggests something more interesting than ‘diversity causes poverty’; all but one of the wealthy countries has few ‘dead’ languages (not in the table – sorry – it occurred to me later). Except for the US, the majority of wealthy countries have preserved their language diversity even though many have undergone very rapid economic growth and have histories of stigmatized language minorities (such as Romani). Mind you, I’m not complicating the picture by raising the issue of immigrant language diversity, which is enormous in some of these wealthy countries, often because of liberal refugee asylum systems, and these language communities can be controversial.

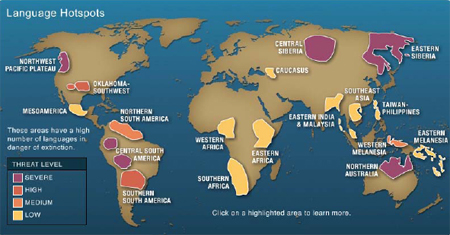

Data can tell many different stories (especially back-of-the-napkin correlations), but I would suggest that Khan’s argument is less persuasive from this data than an argument that say, preservation of language diversity correlates with high GDP per capita. I would need a much larger examination of the dead languages statistics in Ethnologue, but from this data, it looks equally plausible; I would also need to remember my college statisics, probably a more difficult proposition. Moreover, none of the language hotspots that are under threat is in Africa; there are several areas of high language diversity on the continent, but they are not under the same pressure as those in Australia, the US, Canada, Siberia, South America, and Melanesia.

The whole discussion of ‘linguistic diversity leads to poverty’ misses the point, perhaps intentionally. Advocates of linguistic diversity are generally talking about the languages of indigenous peoples within the borders of states that have long histories of oppressing these languages. Khan may think that this is just ‘anthro-jibberish,’ but the historical fact is that in Australia, the US, Canada, Russia (and the Soviet Union), and many South American countries with substantial indigenous populations, majority groups have long sought actively to eradicate these languages or just assumed that they would disappear while simultaneously starving them of support. Khan’s argument is a complete distraction from the actual situations that language diversity advocates are talking about.

Does linguistic difference create conflict?

Khan argues that the only way to preserve language distinctiveness ‘is to put up extremely high barriers to interaction,’ like the Amish, who don’t interact with anyone else (? My late paternal grandmother lived in Iowa around Amish families and there were a lot of Amish people east of South Bend, and I don’t recall either ‘extremely high barriers.’ I recall driving out many times for good pies and excellent wood furniture. But then again, I’m an anthropologist, and I think ethnographic facts are kind of obdurate).

My family is from Bangladesh, which had a “language movement”, which served as the seeds for the creation of that nation from a united Pakistan. Though there was a racial and religious component to the conflict I don’t think it would have matured and ripened to outright civil war without the linguistic difference. Language binds us to our ancestors, and to our peers, but also can separate us from others. A common language may not only be useful in a macroeconomic context, reducing transaction costs and allowing for more frictionless flow of information, but it also removes one major dimension of intergroup conflict.

So language homogeneity not only promotes economic prosperity, according to Khan, but also decreases potential for intergroup conflict. We should let people’s languages die if they’re at risk and the people want to save them because, in the future, they’ll be less likely to fight. People don’t fight with each other if they speak the same language – except in the US Civil War, US Revolutionary War, War of 1812, virtually every war of independence in Latin America, virtually all civil wars, ‘dirty wars’ and low grade conflicts in Latin America (except where the governments sought to eradicate indigenous languages), the conflicts in Korea and Vietnam (remember, it wasn’t all about us – there were two sides of Koreans and Vietnamese in both)… and I’m just pulling these off the top of my head. I’m sure that the slightest bit of research would yield more examples.

Moreover, if language created conflict (and I realize that I’m treating Khan’s more subtle multiple-causation insinuation as if it were a strong theory of causation), wouldn’t we expect to see a lot more conflict? Again, approximately one minute with the Google brought me to the Global Peace Index which suggests that the most peaceful countries, with their number of languages (if not already discussed), are: 1) New Zealand (4, 1 indigenous), 2) Iceland (2, 1 indigenous), 3) Japan (15, multiple indigenous), 4) Australia (274, many dead languages, many indigenous), 5) Norway, 6) Ireland, 7) Denmark, 7) Luxembourg, 9) Finland, and 10) Sweden. A lot of these also appear on our list of wealthiest countries, but the top spots also appear to be disproportionately occupied by island states – not sharing a border is kind of like not having to share the back seat with your little brother, I suppose. And if you thought the Pop/L was skewed by the US in our initial calculation, you should do the numbers with Australia in the bunch!

On the other hand, many of these countries also border on countries with different national languages, presumably without, ‘You say “potato,” I say “prátaí”’ (Irish for ‘potato’) escalating into armed conflict. After all, with over 6000 languages on the planet, one would expect more wars if language was too strong a driving condition. From my perspective as an anthropologist interested in human rights, I’d probably point to excessive arms sales, especially automatic weapons and firearms, into unstable areas; violent nationalist ideologies and other forms of intolerance; and resource-based conflicts, before I’d line up ‘language diversity’ on my list of things likely to cause or exacerbate group conflict.

In a later post, Khan argues that, ‘If you have a casual knowledge of history or geography you know that languages are fault-lines around which intergroup conflict emerges.’ Of course, you might also know that exploitative economic relationships, desire to eradicate a neighboring group, and imperialism also tend to result in testy relations. Why we should point to language as a cause of conflict and then advocate imperial indifference is not clear to me. He keeps saying that the choice is between conflict and assimilation, or between poverty and homogeneity – I just don’t get where the forced choice is coming from except from his theory of decreased transaction costs (what is the language-related mark-up on trade anyway?).

Should we care about language extinction?

In the original Seed article that Khan criticized, Montenegro and Glavin offered one rationale for caring about language extinctions: ‘As cultures and languages vanish, along with them go vast and ancient storehouses of accumulated knowledge.’ This rationale has been put forward, for example, about Aboriginal languages, especially because we know that some Indigenous vocabularies highlight distinctions among plant and animal types that are only now becoming evident to biologists. The disruption of Aboriginal communities and their conduits for transferring knowledge has arguably set back our knowledge of the complicated ecosystems that they inhabited, perhaps irrevocably if these ecosystems are themselves undergoing profound change.

Montenegro and Glavin present research by Italian-born anthropologist and linguist Luisa Maffi as a turning point in the realization that there might be links between decreasing cultural and ecological diversity. Maffi was conducting medical anthropology fieldwork in Chiapas, Mexico, when she met a Tzeltal Mayan man who was bringing his daughter to a clinic for diarrhea care; he remembered dimly that there was once a ‘grasshopper leg herb’ which could cure her, but he no longer could identify it, or perhaps it had become too rare in the environment to support its use. Maffi realized that the world was losing language knowledge of particular species just as it was also losing these local species, in some cases. Maffi went on to form Terralingua, an organization dedicated to fighting for linguistic human rights.

This rationale, we might argue, is the ‘lost knowledge’ anxiety, that languages contain knowledge about the world, a rationale that Montenegro and Glavin point out is ultimately utilitarian (‘save languages because they might be good to have.’). But the point isn’t just that knowledge is being lost to us, Westerners, but that formerly self-sufficient cultures are being subordinated and made less viable, replacing knowledge of locally grown medicinal herbs, for example, with ignorance about any option but purchasing patented pharmaceuticals.

Another reason to care about language diversity is what we might call the ‘lost ways of thinking’ anxiety, that languages contain ways of thinking about the world, cognitive styles, and their own logics. This concern was one expressed by linguistic anthropologist, Benjamin Whorf, which we’ve discussed a number of times on Neuroanthropology.net.

Khan dismisses this argument when it is put to him:

As I told “ana” below a lot of the discussion we had was basically just talking past each other. I kept telling her she was vacuous because she was assuming presuppositions which I simply did not share as empirical background descriptions of the world (e.g., a strong form of linguistic relativism where the specific nature of a language shapes cognition).

Fortunately, theorists in cognitive science and linguistics don’t always share Khan’s dismissive view. But again, this is a utilitarian argument: language diversity is valuable to us so we should encourage it. We need their language so they should be allowed to keep it. Of course, this rationale itself is self-centred; something is valuable only if we think it is useful to us.

More importantly, it’s pretty bold for Khan, a non-linguist and non-anthropologists to tell people in that field,  ‘Naaaaah… nothing to see here.’ To simply declare, with no apparent relevant expertise except reading a book that is of no clear relevance to the issue, that the disappearance of language diversity is no big deal would be tantamount to me, an anthropologist, saying that the disappearance of diversity in oceanic life or the disappearance of most of English literature was really no bid deal. Of course, restraint and staying within one’s area of expertise are not among the higher angels of blogging.

‘Naaaaah… nothing to see here.’ To simply declare, with no apparent relevant expertise except reading a book that is of no clear relevance to the issue, that the disappearance of language diversity is no big deal would be tantamount to me, an anthropologist, saying that the disappearance of diversity in oceanic life or the disappearance of most of English literature was really no bid deal. Of course, restraint and staying within one’s area of expertise are not among the higher angels of blogging.

Montenegro and Glavin highlight a systems view of the importance of diversity, identifying it with the study of ‘resilience.’

It’s the ability of a system — whether a tide pool or township — to withstand environmental flux without collapsing into a qualitatively different state that is formally defined as “resilience.” And that is where diversity enters the equation. The more biologically and culturally variegated a system is, the more buffered, or resilient, it is against disturbance.

For resilience theorists, an excellent example of the dangers of homogeneity might be recent global epidemics of financial crisis. These crises spread, not merely because of interconnection among the world’s economies, but also because of homogeneity; since all futures traders use the same equation to value derivatives and all banks converge on the same reserve requirements and lending policies, any failure to the system quickly ramifies across all components that share the same platform. The contagion of computer viruses, similarly, depends upon the homogeneity of code (and the deadening effect of decreased competition on preparedness for new problems). As Montenegro and Glavin summarize:

Homogeneous landscapes — whether linguistic, cultural, biological, or genetic — are brittle and prone to failure. The evidence peppers human history, as Jared Diamond so meticulously catalogued in his aptly named book, Collapse. Whether it was due to a shifting climate that devastated a too-narrow agricultural base, a lack of cultural imagination in how to deal with the problem, or a devastating combination of the two, societies insufficiently resilient enough to cope with the demands of a changing environment invariably crumbled. The idea is perhaps best summed up in the pithy standard, “What doesn’t bend, breaks.”

But the most important reason to preserve indigenous languages is the one reason that Khan doesn’t seem to consider: Indigenous people want to preserve indigenous languages. If you say to people, ‘You can preserve your language, but we’ll make you poor,’ they might choose to give up their language, but a surprising number do not, even when you add suffering from prejudice and discrimination on top of the cost. But the choice is a false one, one imposed by Khan’s narrow way of seeing the world and language skills.

Khan argues that ‘over the generations there will be a shift toward a dominant language if there is economic, social and cultural integration.’ Like in Europe, for example, where no one wants to preserve his or her own language. Right.

Caring about the causes

To understand the possibility that preserving linguistic traditions might not simply be a librul imposition on the poor people that they hate so much, we need to ask why languages are dying out. Is it simply that people, when they hear it, want to stop speaking their own languages and start speaking Spanish, English, or Mandarin? Ultimately, the discussion of language extinction is about a process that is anything but natural; language extinction has often been an avenue for social domination. Montenegro and Glavin write:

That the Earth is becoming more homogeneous — less of a patchwork quilt and more of a melting pot — is only partly due to the extinction of regionally unique languages or life forms. The greater contributing factor is invasiveness. According to the 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment report, as rapidly as regionally unique species are dying out, rates of species introductions in most regions of the world actually far exceed current rates of extinction. Similarly, the spread of English, Spanish, and, to a lesser extent, Chinese, into all corners of the world easily dwarfs the rate of global language loss. This spread of opportunistic species and prodigal tongues thrives on today’s anthropogenic conduits of commerce and communications.

Khan believes that the days of coercive language change are over. Instead, he argues that contemporary language change is elective, that groups give up local languages when they realize that global dominant languages are the path to material prosperity:

Quite often, and especially today, language change does not occur from on high (in fact, the top-down imposition of standard national languages on the masses is more a recent feature of post-Enlightenment nationalism; Latin spread in the Roman Empire over centuries among the western peasantry). Most Africans who adhere non-world religions are shifting to Islam or Christianity. There is little explicit coercion in this (though a fair amount of social pressure from elites who find Vodun and other native traditions backward).

This is when he brings up the idea that people want to ‘opt-out’ of their own languages. It’s an interesting idea. Khan doesn’t really discuss the imperialist imposition of languages because he assures us that these bad ole days are over. Now, people are choosing to let their languages die.

Okay, let’s leave aside for a moment the issue of forced language change, of imperial powers that demanded minority groups speak the dominant language. Let’s just forget for a moment that Indigenous groups have often been denied education in their own languages, marginalized in legal and political process without dominant language abilities, even had their children taken away from them and been punished for speaking an Indigenous language. Let’s just, for a moment, ignore the fact that Indigenous people have been identified by language and subjected to oppression, persecution and even genocide for it. For the sake of argument, I’ll grant Khan this for the moment and say, ‘Let bygones be bygones! Today, people only change their languages because they want to and no one wants to be stuck with a lousy local Indigenous language when they can have a shiny dominant global language.’

Do people want their local languages to go away?

Several logical and empirical problems dog the assertion that people just want to get down with the global languages: first, if folks don’t want to preserve their local languages unless hysterical liberals put them up to it, why are the people on Faroe Island speaking Faroese, or anyone at all speaking Luxembourgish, Bokmal Norwegian, Nynorsk Norwegian, any of the Sammi languages, Romansch, Greenlandic, Finnish or Swedish? I mean, c’mon, these folks have got some cash in the pocket – why don’t they just drop these distracting languages and get with the Globish? And what about Hebrew? And why the heck would otherwise right-minded people in prosperous parts of he world be trying to revive or revitalize Scottish, Maori, Aragonese, Celtic, Cherokee, Cornish, Basque, Navajo, Catalan, Gascon, and Hawaiian, let alone teaching themselves Klingon or Tolkeinese?!?

The point is, when people have resources, even if they have access to global languages, they often vote with their tongues for the preservation, revitalization or even creation of languages that are meaningful to them. In many places around the world, even poor countries have done the same: Papua New Guinea, for example, has found that it’s possible to have primary education in hundreds of languages, and Native American languages are increasingly used for education throughout the Americas. These programs are seldom top-down, imposed programs of liberal guilt – there just aren’t enough guilty liberal language teachers of rare tongues around to make this happen.

The leadership may be led by local elites, true, and they may ally themselves with outsiders, like anthropologists, but the idea that libruls everywhere in the impoverished world are forcing Francophile Indigenous kids or Spanish-loving Native Americans to study their local languages – oh, no, not that white ma’am speaking Tlingit again! – is clearly a figment of Khan’s imagination.

In fact, for left-leaning intellectuals, the recognition that Indigenous peoples wanted to stay ‘indigenous,’ in language and culture, came as a bit of a shock; raised on earlier Marxist-inspired understandings of liberation, mid-twentieth-century radicals often assumed that these languages would disappear to as poor Indigenous people became International Workers. Psssst, Razib, Indigenous rights are not a liberal conspiracy, they’re an Indigenous conspiracy: some people call it ‘self-determination.’

Can we help stop language extinction?

The point is that to save many of the world’s endangered languages, we don’t need the speakers to change; we need to change. They’re already speaking these languages, trying to get the right to have their kids go to school in the language that the speak at home and in their communities. These languages are not disappearing because people are spontaneously making rational decisions to drop their old languages and get down with the global argots; these languages are disappearing because populations around them are actively undermining or, at the very least, callously doing everything else to make these languages unviable. The crisis of decreasing linguistic diversity, like the decrease in biodiversity, is an imperial side-effect, not a failure of indigenous communities.

Can indigenous languages be saved? Absolutely. We’ve seen a number of revivals and revitalizations of Indigenous and ‘small’ languages in North and South America, the Pacific, Europe, New Zealand, and Asia. We’ve seen communities proudly starting language classes in traditional languages with no seeming ill effect on their ‘utility,’ or ours, the speakers and writers of majority languages, for that matter. Is language revitalization undermining the quality of written and spoken grammar? Not half as much as texting.

Can indigenous languages be saved? Absolutely. We’ve seen a number of revivals and revitalizations of Indigenous and ‘small’ languages in North and South America, the Pacific, Europe, New Zealand, and Asia. We’ve seen communities proudly starting language classes in traditional languages with no seeming ill effect on their ‘utility,’ or ours, the speakers and writers of majority languages, for that matter. Is language revitalization undermining the quality of written and spoken grammar? Not half as much as texting.

Will we, Western speakers of dominant languages (if that’s not you, I beg your pardon), work to save other languages if we don’t change our attitudes? Of course not. But isn’t that the point? Some Westerners have convinced themselves that the cure to the world’s ills is for everyone to become more like them, and they’ve set about making that vision a reality with some pretty coercive means. But the problem is, if everyone else consumes like us, farms like us, mines like us, burns fossil fuel like us, and, yes, talks like us, we’re going to run out of the space we need to support even us. The whole point of the movement for biocultural diversity is to realize that we, those speakers of dominant languages, need to change.

Increasingly technology is making it possible to overcome language differences and communicate in spite of using multiple dialects. Low-cost local media can support linguistic minority communities, as can locally-produced educational materials. We know that students are more likely to succeed in school, to graduate, and even to do well in dominant-language classes, when they get a substantial part of their education in their mother tongue.

Besides, it’s estimated that more than half of the world is bilingual or polyglot, including plenty of people who are both extremely poor and quite well to do. Learning multiple languages is just not that hard; in some societies, virtually everyone does it.

I would say that Khan has got the argument precisely backwards; languages don’t die out because poor people want to become wealthier. Languages die because people are too poor (or too dominated) to maintain them. Westerners or colonized elites often make shedding language and minority culture a precondition of interaction. If they have the resources they need and under no coercion, virtually no group voluntarily sheds its language; they may learn second languages, but I know of no case where a group spontaneously decided to switch languages (although Fiji did recently switch which side of the road they drove on – more used cars available on the other side). If anything, people produce more literature, more poetry, more radio broadcasts, and more webpages in their first language. Of course they want to learn global languages, but the point is that it’s not an either/or choice.

If dominant languages were so great, so infinitely superior to local languages, then global languages should spread on their own, without coercion. To some degree, they do — we find English as a second language around the globe, especially among the educated and upwardly mobile. But to assume from this fact that everyone should just learn English because your theoretical model of transaction costs predict they would be better off, even though people are clearly indicating through their own actions that the cost-benefit bundle of their own native language is the way to go is believing in your model more than the evidence of reality.

The big reason: it’s not us, it’s them

A number of Khan’s online respondents, and his own statements, imply that the motivation for preserving indigenous languages is a kind of liberal guilt. So, go ahead, they seem to suggest, ‘off with the rest of ‘em!’ As one knuckle-dragger remarks: ‘On a side note, I had a friend in my undergrad years who felt that the English language was a vehicle of atrocity and imperialism (hehe, to paraphrase that saying “you would have to have a college education to say something that stupid).’ He he. That’s so funny. No, enforced language has never ever anywhere been a problem. He he. You’d have to have a college education to say something that stupid. (Lovely, too, that Khan then makes a crack about the commenter’s friend being ‘retarded.’)

So let’s talk about this ‘stupid’ idea that preserving language might be somehow linked to imperialism. Khan’s anti-diversity, anti-human rights argument is that language preservation is simply a form of amusement for the wealthy whose cost is imposed on the poor who actually speak these languages. As he puts it, ‘The cost of collective color and diversity may be their [the speakers of minority languages] individual poverty…’

In fact, the discussion of language diversity is a crucial front in the debate about how to make real the rights of Indigenous people after some staggering acts of callousness, cruelty and neglect toward them. Leftists did not put language preservation on the human rights table; Indigenous people did. To treat the language diversity discussion as if it were just an elitist and paternalistic concern both disregards one of the most important frontiers for human rights and involves convenient amnesia about the legacy of imperialism and even genocide (or ‘culturecide’). To me, the decrease in language diversity is not the problem itself, but a kind of global indication of how the numerous wars on minority groups are going, even if those wars are simply sieges of neglect and indifference. Decreasing linguistic diversity suggests that pressures to lose language, impediments to transmitting local languages, are still in place, in spite of what Khan might want to believe. The fact that so much linguistic diversity exists in wealthy countries suggests that the choice between prosperity and language diversity is a false one.

In other cases, loss of language diversity would signal the eradication of a community. For example, one of Khan’s commentators points out the case of the Andaman Islanders; because they are hostile to outsiders and wish to be left alone, the disappearance of this language would signify the disappearance of the group, through some sort of small-scale, but extremely profound demographic catastrophe.

The most important thing that Khan gets wrong is the simple fact that people care about their languages and, given a choice, choose to preserve them, even at some cost to themselves. They demonstrate with their own investment of resources and energy that it matters, enough so that Indigenous groups and other groups have repeatedly struggled to get these rights recognized in scores of countries. Khan doesn’t bother to even acknowledge this historical fact, dismissing the possibility that people could care about language. He implies that the philosophical foundation for protecting linguistic diversity is a misplaced liberal celebration of diversity for its own sake when it’s actually respect for hard-won human rights. Don’t ask me, Khan, look in the relevant UN and human rights documents!

The most important thing that Khan gets wrong is the simple fact that people care about their languages and, given a choice, choose to preserve them, even at some cost to themselves. They demonstrate with their own investment of resources and energy that it matters, enough so that Indigenous groups and other groups have repeatedly struggled to get these rights recognized in scores of countries. Khan doesn’t bother to even acknowledge this historical fact, dismissing the possibility that people could care about language. He implies that the philosophical foundation for protecting linguistic diversity is a misplaced liberal celebration of diversity for its own sake when it’s actually respect for hard-won human rights. Don’t ask me, Khan, look in the relevant UN and human rights documents!

In fact, language preservation does involve thinking about past genocide, realizing that language extinction is a form of burying the body, hiding the remains, or scrubbing the evidence. Preserving endangered languages, or at least helping the communities that want to preserve their endangered languages, brings up some awkward questions to which Social Darwinism offers convenient answers. Languages will always go extinct, but hurrying them along because they’re inconvenient to us is a bit like the undertaker or mortician in Monty Python’s ‘The Holy Grail’ dispatching the man with the temerity to say he’s ‘not dead yet!’ Khan’s approach is to tell them to get on with the dying because they’ll be better off afterward, when their cultures are gone – more utility in that, you know.

Providing people with the right to educate their children in the language of their choice is a bit like allowing the memory of the crimes of empire to be told. To see these languages flourish is to find signs that our world has become more open to groups’ desires for self-determination and less inhospitable for minorities. For those among us who care about human rights and justice, hearing a rare language should be a gratifying reminder that it’s still possible to choose to carry on one’s own tradition, that the choice to preserve diversity is not bought with a condemnation to poverty or isolation.

Ultimately though — and I think that no matter whether you disagree with me on the previous points our not, this is crucial – the decision about whether or not to preserve a language is in the hands of those who speak it. Khan and other critics of the linguistic diversity movement seem to deny that this should be where the decision must be made, even though they often accuse the linguistic diversity movement of being ‘paternalistic.’ Ultimately, anti-diversity proponents cannot imagine that other people would not choose to become like us, interact with us, or at least to understand the language of dominant people, so some of these proponents want to eliminate even the possibility of making a choice. When the language is gone, the choice will be, too. Anti-linguistic diversity advocates do not recognize the costs of learning a dominant language or the costs of losing one’s own tongue. Market advocates tell us that we should trust people to make their own choices, as this is the only way to ‘maximize utility.’ Telling people what is good for them, telling them what will make them most happy, is a command economy. If there’s a cost to remaining ignorant of world languages, and people choose to bear that cost, that is, by definition, their utility maximizing position.

Saying that you want to help people, but only on the condition that they give up what makes them distinctive – something that plenty of rich countries demonstrate is no impediment to being successful – is holding their well-being hostage to your ideology and desire to make others like yourself. This conditional approach to development is anti-human rights, but it’s also anti-self determination and even anti-market. It’s just old fashioned cultural imperialism dressed up with some economic jargon: what’s wrong with you is that you’re not like me. Let me fix that. Khan may openly admit that he’s Eurocentric, but I don’t really think he’s considered the other implications of what he’s arguing.

Razib Khan on cultural anthropology: Now, it’s personal

I’ve just got to make a few comments on Khan’s attitude toward anthropology, which seems to me to display a certain bipolarity. First, Khan doesn’t feel the need to respond to cultural anthropologists who argue with him (please continue this policy with my post, Razib — thank you):

As for my critics, note that I don’t really engage them directly, because the theoretical frameworks we use are so distinct. They misunderstand me, and I misunderstand them (honestly, I have no idea what they’re saying most of the time in the broad sense, aside from the fact that they’re offended).

True, Khan, well-trained, well-read anthropologists have a tendency to use technical terms that you might not have come across in your biological education, I’ll admit, but I suspect that you, too, use a few bits of jargon here and there, sometimes even when you don’t need to (although I’m surprised that in all your reading about cultures, you haven’t picked up the basic gist of what we’re saying). Fair enough, but I believe that some of us are actually understanding you much better than you suggest. Khan continues: ‘I have as much respect for most American cultural anthropology as I do for Talmudic scholarship; I’m sure they’re bright individuals, but they aren’t doing anything which I think relates to a world outside of the minds of the practitioners.’

This critique – that what anthropologist do does not relate to a world outside their minds — is pretty rich coming from a science blogger who works online, probably sitting at a desk and clearly not reading much of what anthropologists write (leaving aside the Talmud). After all, cultural anthropologists have to do things like, well, go outside, to do their research. Anthropologist often actually go live with poor people (as opposed to just smell them, Razib), talk to them, learn their languages, advocate on their behalf, and then try to persuade fellow Westerners that their lives and opinions are worth considering.

Ironically, in a final post that I only saw as I finished this, Knowledge is not value free, Khan tries to say that he’s especially fascinated with cultural diversity and reads monographs on different cultures (are they written by non-anthropologists? He keeps linking to Wikipedia, so I don’t know):

I’m not someone who has no interest in the details of ethnographic diversity. On the contrary I’m fascinated by ethnic diversity. Like many people I enjoy reading monographs and articles on obscure groups such as Yazidis (well before our national interest in Iraq) and the Saivite Chams of Vietnam. Oh, wait, I misspoke. I actually don’t know many people who have my level of interest in obscure peoples and tribes and the breadth of human diversity.

He then goes on to suggest that, if you share his extraordinary interest in obscure peoples, as well as his disdain for the fate of their languages, you should contact him for coffee if you swing through his locale. (If you need an RSVP, Razib, I can’t make it.)

The hubris and just, well, confusing illogicalness of saying that the Western academic attempt to understand other world views through direct research doesn’t ‘relate to a world outside of the minds of the practitioners’ is pretty bold, but then talking about how much you enjoy reading about other cultures is, well, bizarre and a bit bipolar. Don’t let the facts get in your way, I say. You may not like the way we write, Khan, but at least grant us the courtesy of recognizing what we do for a living. I daresay it’s less isolated from ‘a world outside of the minds of the practitioners’ than, well, professional blogging, for example.

You may have smelled poor people when you went to Dhaka, but anthropologists actually go live with them, sometimes for years at a time, or longer. If you too have done this, great, but anthropologists try to return the hospitality they are shown with something like compassion and concern for those who make our work possible. Rather than just pontificate on what minority groups or Indigenous people might want, we sometimes do crazy things like ask them. The fact is that anthropologists are disproportionately involved in human rights causes, including Indigenous rights, not because we’re closet totalitarians who hate poor people and want them to be our own human zoo, but because we’ve spent enough time with them that we feel some responsibility to them. If you can’t hear Indigenous people’s desire to preserve thing like language and culture, I’d say it’s because you haven’t bothered to listen. Disagree with us, but don’t just pitch the hackneyed anti-intellectual argument that anyone who doesn’t talk like a sports commentator is living in splendid isolation atop an ivory tower.

In his final post on the subject, Khan writes that when he posted his original discussion of the language diversity-utility chart, ‘I did mean to provoke, make people challenge their presuppositions, and think about what they’re saying when they say something‘ (emphasis in the original). I just wish Khan would do more of the same himself. I find the four posts fluctuate insecurely between callous disregard and a kind of smartass disrespect for an issue, and then when he’s called on it, a kind of confused whining about how he really does care. This pattern is the classic thin-skinned sensationalism of the ‘provocative’ opinion writer: say something outrageous, and then when called on it, walk it back while acting like your critics haven’t been generous enough with you or taken enough time to understand you.

My advice to Khan is, if you’re going to say dismissive things about issues that you clearly realize are profoundly important to people – like human rights or Indigenous rights or the preservation of cultural diversity – grow some thicker skin, or maybe secrete a hardened carapace of some sort. Saying that the process of language disappearance is natural might be partially true, but that’s like saying that ecosystem degradation is the natural outcome of agriculture. The word ‘natural’ is incoherent and ideologically loaded, a way of smuggling in the assumption that humans have no choice about their own actions. (Note: If this is confusing, ask yourself if agriculture is ‘natural’…)

We can choose to care or not to care about the disappearance of languages; but we, Westerners, liberals and non-liberals alike, can’t choose to prevent their extinction because that process is not entirely under our control, much like species extinction. We can choose, however, to try to make this more or less difficult for those who will choose about whether to carry on a tradition. Caring about linguistic diversity means caring about the autonomy of minority groups, and they may (MAY) choose not to preserve their own languages. But we can choose to look the other way or even speed the process along, especially by trying to persuade ourselves that we’re really doing what’s good for the people whose autonomy we most need to respect.

More on Razib Khan and the ‘bright side of language loss’

Chris, The Lousy Linguist, has also posted a note on the piece at Gene Expression: the upside of language death?

Society for Linguistic Anthropology, Linguistic Anthropology Roundup #10, comments on one of the posts.

Creighton’s blog, Linguistic diversity does not equal poverty

A replicated typo, Some Links #11: Linguistic Diversity or Homogeneity?, by ‘wintz’ (James Winters)

John Hawks, Language Loss

Website for Terralingua, an organization dedicated to biodiversity and cultural diversity.

Graphics:

Linguistic diversity hotspots map from National Geographic

Originally from the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/mission/enduringvoices/

Languages spoken in the Americas map from Wikimedia

By Bob the Wikipedian

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Languages_of_the_Americas.PNG

‘Freedom blues’ cartoon from Linguistics Cartoon Favorites: Linguist Sings the Blues

Savage Chickens cartoon from the brilliant Savage Chickens — Cartoons on sticky notes by Doug Savage

If you follow no other link, this is the one you should click…

References:

Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

well, you haven’t really convinced me on the *specific question*, but i’ll grant i was being a dick 🙂

oh, and tell me *which* post and i’ll remove the links since you asked. i’m all about increasing utils 🙂

Thanks, Razib —

I’m specifically referring to the line: ‘Extreme projects in cultural relativism, and fixation on semantics, tells us more about the psychology of WEIRD people than anything else.’ Which appears at page:

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnxp/2010/07/linguistic-diversity-other-views/

It’s particularly frustrating because the whole article by Henrich and colleagues, and my response to it, is about the dangers of generalizing from WEIRD subjects to the whole of humanity. Henrich and colleagues are precisely putting their finger on an under-examined form of intellectual ethnocentrism.

I hope you can understand that it would then be very frustrating, very very frustrating, to then find someone citing this discussion to say that concern about Indigenous peoople’s languages is likely a kind of WEIRD bias or concern. Anthropologists get understandably irritated, especially in the realm of human rights-related work, when people from the West who don’t have the same kind of knowledge of small minority cultures tell the anthropologists that their concerns are simply a kind of liberal projection.

I won’t place irritated comments on your own blog, but I really think that you should consider before dismissing too quickly the long struggle for indigenous cultural and linguistic rights around the world, in many locations (my own knowledge is primarily about Latin America and, increasingly, Australia). I agree that the argument for diversity being linked to resilience is stretched when applied to linguistic diversity, but the arguments for protecting language rights from respect for autonomy, self-determination, protection of minorities and justice are all quite strong. I just don’t understand why someone who cares about cultural diversity, as you say you do, would be scornful of one of the leading edges of cultural rights movements — land, language and self-determination are the foundation of Indigenous rights.

1) link gone

2) i’m a big fan of heinrich’s work, and have been familiar with it for a while and the critique of modern economics and psychology.

3) but, there’s also the aspect of human universality. the two need to be balanced. rational actor models of economics push the pendulum too far in one direction, assuming that all individuals are interchangeable for analytic purposes (they don’t literally believe this, but assume that the models with this assumption are robust in capturing real phenomena). OTOH, i see a lot of cultural anthropology pushing in the other direction, assuming too much incommensurability.

4) i won’t push this too far because you find the accusation offensive, but yes, i think that modern cultural anthropologists are operating out a framework which derives from western culture, and a post-westphalian conception of national and human rights. some of this is an extrapolation of human universal concepts (or abstractions and extensions), but i believe a lot of it is culturally specific (though i think specific aspects of european culture as it developed in the 20th century are spreading to become universal). additionally, values and information do flow between societies, and the people who you interact with are evolving and absorbing as much from you as vice versa (the case of the expansion of quechua AFTER the spanish conquest at the expense of other indigenous languages in the highlands is to me a classic case of the complexities dichotomy that i see in your field between “euro” and the “indigenous).

5) “I just don’t understand why someone who cares about cultural diversity, as you say you do, would be scornful of one of the leading edges of cultural rights movements — land, language and self-determination are the foundation of Indigenous rights.” because i believe cultural diversity increases my own well-being because of my interest in specific instantiations of general human cultural dynamics. my life is one of the mind, so the contribution of extant variation is concrete to my happiness. i do not think that cultural diversity necessarily leads to the long term flourishing of individuals and societies though. i can accept a balance between group and individual human rights, but i perceive that your discipline collapses the distinction too much. to some extent the distinction is one of semantic book keeping, as one reduces to the other, but not always. as a concrete example, i have shown that the genetic data are clear, and 20 times as much of the genetic material distinctive to native americans in brazil is found within people who do not identify as native american (white, brown and black brazilians) as opposed to the minority who do. the native ancestors of white, brown and black brazilians (mostly women by the genes) lost their distinctiveness in a cultural-ethnic sense, but were co-opted and absorbed into the majority non-indigenous luso-brazilian matrix. but arguably their descendants live at a much higher level of economic well being. in a utility calculation i think the trade off here is one that is open to discussion. generally what is examined in detail is the real cultural genocide, the negative aspect of the ledger, as opposed to the demographic assimilation, arguably the positive component.

i am actually going to attempt a rigorous presentation of the data in scatterplots which you skimmed (though i’m probably going to calculate my own indices of diversity drawn from information theory if i can’t find tables). i’m skeptical that we’ll control well for variables, and i don’t think the arrow of causality is simple. i’ll also avoid casting aspersions on your discipline for what it’s worth. being an asshole has its upsides and downsides. but my main audience really aren’t cultural anthropologists or those who follow the work of the discipline. it’s people who haven’t thought of the issues in detail, and have never had an interest in them. i do have a genuine interest in cultural variation, but my normative and methdological framework is so at variance with yours that i’m more interested in developing an alternative intellectual ecology. though when cultural anthropologists engage in formal model building or collaborate with behavioral economists, psychologists, etc., you’re intelligible to me.

Thank you for this comprehensive response.

When you have a moment, do drop by at my blog (in English) on linguistic human rights and education, Bolii. (There’s also an Esperanto one called Lingvo kaj vivo.)

Giri RAO

Hyderabad, India

There’s something to what Razib said.

He is a Bengali. He knows that many South Asian parents sacrifice to send their children to English language schools. English is the passport to good jobs, whether in South Asia or the US/UK/Canada/Australia/NZ.

English also has a political use: speaking it doesn’t align you with any one community. Language differences have been extremely divisive in South Asia, as Razib noted. Yes, English is a legacy of colonialism — but it’s not colonialism enforcing English use these days, it’s the South Asians themselves. They find it USEFUL.

He also notes, correctly, that the language of the ruling class, in long-enduring empires, tends to crowd out other languages. English, Spanish, French, Dutch, Mandarin, Arabic, Persian grow and the languages of smaller communities retreat. This isn’t solely due to oppression. The Romans, frex, had absolutely no interest in teaching their subjects to speak Latin. As long as the peasants paid their taxes and kept their place, they could speak as they pleased. But if the peasants wanted to trade in a big city, or communicate with other Roman subjects from other language communities, Latin was the best choice. When society gets bigger, the bigger language is more useful.

Recently I read an interesting comment about the language of Indian movies. The producers want to target the biggest language community within their market area; best return on the rupee. That means that speakers of small languages don’t get to see many, or even any, films in their own language. If they want to take in a movie, they need have some competency in Hindi or Tamil or another of the larger languages. Multiply that sort of dynamic in many areas of life, over many years, and you’re going to see shrinkage in small languages — no oppression needed.

Greg, Razib is taking a very long view of history, while you seem to be focused on the last 100 years or so. Yes, with the rise of nationalism as an ideology we see attempts to enforce the use of national languages and stamp out smaller tongues. But that has not been the case for most of human history.

I agree, Zora, and I always regret, to some degree, blogging while angry, but Pam (in a latter comment) is right: this idea that language extinction is okay is seeming to circulate a lot right now. I don’t doubt what she says, that it might be linked to battles over language of instruction in the US (and probably similar issues in Europe and elsewhere).

And like you, and Razib, I realize that the contemporary dynamic for language extinction is not driven by persecution or imperial imposition. It’s having everything around you slowly turn into the dominant language, from the television to your kids’ rap music to the names on products to the movies in the local cinema. No oppression is necessary. In fact, many times throughout history, dominant groups have tried to eradicate languages, either because they sought to eradicate the groups that spoke them, assimilate these groups, or just wipe out remnants of a defeated enemy. Now, the dynamic is less coercive, more seductive.

In addition, I agree, in the long run — and this is John Hawks point — language extinction is the pattern. Of course, so is language creation. Heck, in the long run, biological extinction of species is the pattern, but it’s hard to find people suggesting that human extinction is not a big issue, or trying to hurry it along (movie villain characters notwithstanding). In the long run, English will be replaced by whatever comes next, as will most languages.

What I object to is the assumption that, since language extinction is normal, we shouldn’t help those who wish to try to preserve a language, especially because many of these languages are not on the brink of extinction because of ‘natural’ forces, they are there because, for generations, people have not allowed to educate their children in their own languages, see media in their own languages, or use their own languages outside their homes without fear of stigmatization or outright harassment. For example, in Australia, where I live, we can’t just say, ‘Aboriginal languages are dying. Don’t know how that happened. Oh well.’ That’s amnesiac as well as profoundly cruel. And it’s not just liberals who want to save languages; without the interest of the speakers themselves, this movement would have zero steam to get off the ground.

My point, which is admittedly in there somewhere, surrounded by about 9000 other words, is that, given the history of language suppression, given that these groups themselves only want the right to use their own languages, given that they are willing to bear the ‘price’ of this decisions to not fully assimilate, who are we not to offer them a bit of help, or at least not to say to them, ‘yeah, we drove you to the brink of extinction, but we’re just going to laugh at you when it happens.’ Perhaps compassion is hard to fire up people about in blog posts, but coming from a human rights perspective, it would be nice if we could help people who could really use a bit of help do something that means a lot to them.

The anger and frustration that everyone can detect in this post, the reason I use the word ‘callous,’ is that I think it is callous to look at the survivors of these groups, the ones who have clung to these ways of life in the face of cruelty and indifference from far-more-numerous, far-richer colonizers and just say, ‘naah. Not going to help. You’re going to die anyway.’ I do think that perspective is callous. Yes, previous empires have smashed their enemies, erased the existence of those they have conquered, and forced the defeated to take up the triumphant way of life. We haven’t learned anything from this?