Or, confronted by the yawning gap between elite athletes’ performances and the ability of the average person, sceptics still want to focus on the slight differences among elites athletes (for example, Jon Entine’s book Taboo), suggesting that this tiny fraction of difference is the ‘innate’ part, the ‘talent.’ I can describe the years of arduous labour that go into producing elite-level achievement, the countless hours of training and sophisticated coaching, and someone will inevitably say, ‘Okay, but some people are just inherently good at sports, aren’t they?’

But as psychologist K. Anders Ericsson said in an interview in Fast Company (cited here by Dan Peterson), ‘The traditional assumption is that people come into a professional domain, have similar experiences, and the only thing that’s different is their innate abilities. There’s little evidence to support this. With the exception of some sports, no characteristic of the brain or body constrains an individual from reaching an expert level.’

Obviously, certain dimensions of the body can affect one’s ability to participate in a sport like basketball or sumo at an elite level, or a genetic abnormality may create an unusual wrinkle in a metabolic or even a neural process, but research like Ericsson’s suggests that these sorts of traits are likely the exception rather than the rule. That is, even if there is a genetic trait that helps some Kenyan runners to excel, or gives an individual with photographic memory, or helps a free diver to endure oxygen deprivation, these cases do not confirm the folk idea that talent is innate (and thus likely genetic).

In this post, I want consider the difference that makes a difference. That is, how the concept of talent itself actually affects the unfolding and compounding of developmental variation, helping extreme ability to emerge (and de-motivating those who don’t demonstrate early ‘promise’). Whether or not ‘talent’ exists—and I’m profoundly skeptical—believing that it does is a good foundation for exaggerating variation in skilled ability.

What is talent and how to identify it

‘Talent’ or ‘potential’ are ways that some of us think about inequality in ability, or variation in the way that different people seem to benefit from training. ‘Talent’ is alleged a potential trait, a symptom of nascent ability, a foreshadowing of future greatness, or a way of explaining someone’s early achievements or performance advantage. On the other hand—paradoxically—the concept of talent is a way of understanding why some experts are more proficient than others; unlike a concept like jeito, a Brazilian term for something like a ‘knack,’ ‘talent’ is usually quite task specific or specialized, even though a ‘talented’ person is often quite versatile.

‘Talent’ is typically contrasted with ‘hard work’ or ‘determination,’ suggesting skill is some mix of natural ‘talent’ and ‘hard work,’ in various proportions. The cultural concept of ‘talent’ is a bit unstable; no one would expect a talented musician to simply pick up an instrument and play. Rather ‘talent’ is usually an idea that some people learn quicker, more effortlessly, and with greater effect. In some ways, ‘talent’ can be like a multiplier, allowing a person to get more out of formative experiences and instruction.

At times, ‘talented’ seems to mean little different from skilful, but ‘talent’ also has a bit of an edge: it can be an evaluation tinged with disappointment, ‘squandered talent,’ a suggestion that a person has potential which may not have been fully developed because of other failures, like an absence of hard work or discipline.

In sports, there’s sometimes the suggestion that ‘talent’ might have biological or even genetic roots, although there is little evidence (yet?) to support this assumption. We sometimes think of talent as running in families, one way to explain sports dynasties other than role modelling, expert in-house coaching, or increased opportunities from association with a successful predecessor.

Howes et al. (1998:2) offer five properties alleged to be true of ‘talent,’ and compare each with extant research that either demonstrates or undermines these propositions implicit in folk ideas of ‘talent’:

1. It originates in genetically transmitted structures and hence is at least partly innate.

2. Its full effects may not be evident at an early stage, but there will be some advance indications, allowing trained people to identify the presence of talent before exceptional standards of mature performance have been demonstrated.

3. These early indications of talent provide a basis for predicting who is likely to excel.

4. Only a minority are talented; if all children were talented, then there would be no way to predict or explain differential success.

5. Talents are relatively domain-specific. (This summary of Howes et. al. 1998, appears in Helsen et al. 2000: 728).

An entire specialized research literature, much of which is not published but held privately by various sports organizations, is dedicated to ‘talent identification,’ to the incredibly difficult business of figuring out which young athletes will reward serious investment of training resources. Especially as states spend scarce resources trying to achieve high prestige athletic outcomes, most extravagantly focusing on Olympic medals, the energy and research focused on talent identification, already great, is likely to increase. And judging from what I’ve read, this is still likely to be a hit and miss endeavour for reasons that will become clear .

For example, the Australian Sports Commission provides a series of resources intended to help coaches identify promising athletes as young as twelve years of age. Their website has a self-administered eTID, an electronic talent identification test.

eTID is the brainchild of the Australian Sports Commission’s successful National Talent Identification and Development (NTID) program which seeks to identify and develop Australia’s future sporting talent. This interactive website allows users to enter in results for a series of simple ‘home based’ performance tests and measurements which can be used to help identify athletes for selection in NTID development programs….

If your results are identified as above average you will be encouraged you to visit a Talent Assessment Centre (TAC) to have your results verified. After assessment, you may then be able to enter the elite sporting system, where you could be supported with coaching, equipment and travel.

Likewise, in the lead up to the 2012 Olympic Games in London, UK Sport has rolled out an ambitious talent identification program, but these sorts of programs are hardly knew; ‘talent identification’ and state support for athletic training was a battleground for prestige during the Cold War, producing generations of world class athletes, sometimes in conditions that amounted to gilded slavery.

But talent identification is tricky business, and it’s unclear whether tests or screening do anything other than confirm what coaches and spectators already know (‘hey, that kid is fast), or expose physically fit kids to sports that they might otherwise not consider doing. Neither of these two really confirms that ‘talent’ exists; one simply means that people who are good at athletics tend to stay good or get better with support, the other that skilful athletes are sometimes better than other beginners at sports they’ve never tried. As the SPARC-commissioned Talent Identification and Development Taskforce of New Zealand reports:

The Taskforce’s conclusion, consistent with findings by sports science researchers world wide, is that there is no simple way to accurately identify future talent as talent is multi-dimensional. It can emerge at any point during an athlete’s development, and is affected by factors such as genetics, environment, mental, physiology and support. However, it is possible to create an environment that increases the chances of athletes fulfilling their potential.

That is, in other words, we don’t know exactly what it is or how to identify, or even when exactly it would show up, but we know talent exists. So we should give everyone support because eventually, we’ll see who gets good and those are the ones with talent. Fair enough, but hardly proof that ‘talent’ even exists.

Some of the examples of successful ‘talent identification’ in sports are hardly compelling proof that we are close to some consistent diagnostic for talent. Stories about successfully converting sprinters with good upper body strength into pushers for an Olympic bobsled, or of training a champion beach sprinter who must accelerate in slippery sand and dive after a baton into a world-class skeleton rider who must accelerate on slippery snow until diving onto a sled face first, hardly demonstrate a penetrating perception of untapped athletic ability. In fact, it’s more likely a commentary on how core techniques may be closely related in diverse sports.

Studies of expert performance

Although the idea that excellence is innate, at least as some kind of hard-to-define ‘potential,’ dies hard, research by psychologist K. Anders Ericsson strongly suggests that skill emerges out of deliberate practice rather than being born in a person.

Popular lore is full of stories about unknown athletes, writers, and artists who become famous overnight, seemingly because of innate talent—they’re ‘naturals,’ people say. However, when examining the developmental histories of experts, we unfailingly discover that they spent a lot of time in training and preparation. Sam Snead, who’d been called ‘the best natural player ever,’ told Golf Digest, ‘People always said I had a natural swing. They thought I wasn’t a hard worker. But when I was young, I’d play and practice all day, then practice more at night by my car’s headlights. My hands bled. Nobody worked harder at golf than I did.’ (Ericsson, Prietula and Cokely 2007)

When most people practice, they focus on the things they already know how to do. Deliberate practice is different. It entails considerable, specific, and sustained efforts to do something you can’t do well—or even at all. Research across domains shows that it is only by working at what you can’t do that you turn into the expert you want to become.

The problem for many people is that they’re not practicing deliberately; if they did, they would see a bigger improvement in their performance.

Ericsson and Lehmann (1996), for example, discuss a host of studies that converge on the realization that ‘talented’ individuals take virtually the same amount of time to achieve expert performance as their less gifted colleagues, we just don’t tend to notice it. The physical and neurological traits necessary for expert performance tend to be the result of, not the precondition of, increasingly skilful performance and this extended apprenticeship in physical techniques (Ericsson and Lehmann review a host of examples, such as ‘perfect pitch’ in music, chess ‘prodigies,’ ballet ‘turn-out,’ and ratios of fast twitch to slow twitch muscles, all of which appear malleable given the right timing and conditions).

An article in The Australian describes how Ericsson’s research undermines the idea that ‘talent’ exists at all:

Ericsson’s theories confound the beliefs of thousands of years. Now as Conradi eminent scholar at Florida State University in Tallahassee, where he has been based since 1992, his basic argument is that there’s probably no such thing as innate talent or, if there is, it’s overrated. The only thing he will allow is that very occasionally certain physical gifts, such as height in a basketballer, will help. But in every other case, what’s at work in such massive successes as golfer Woods is a complex cognitive process that pushes the body and mind to extraordinary heights. (From ‘Success is all in the mind,’ by Shelley Gare)

In fact, Ericsson and Lehman suggest that the kinds of basic testing involved in much ‘talent identification’ may not be an indicator of success at specialized, skill-demanding activities:

Reviews of adult expert performance show that individual differences in basic capacities and abilities are surprisingly poor predictors of performance (Ericsson et al. 1993, Regnier et al. 1994). These negative findings, together with the strong evidence for adaptive changes through extended practice, suggest that the influence of innate, domain-specific basic capacities (talent) on expert performance is small, possibly even negligible. We believe that the motivational factors that predispose children and adults to engage in deliberate practice are more likely to predict individual differences in levels of attained expert performance. (Ericsson and Lehmann 1996: 281)

Even in seemingly simple tasks that would require basic differences in neurophysiology, ‘talented’ individual don’t tend to measure that differently from normal people on general measures. For example, ‘Numerous studies of basic perceptual abilities and reaction time have not found any systematic superiority of elite athletes over control subjects,’ even in athletes doing high speed interception tasks, an area where we might expect to find these differences (Ericsson and Lehmann 1996: 280; see also Abernethy 1987; and Starkes and Deakin 1984 for reviews). Legendarily, for example, Sir Donald Bradman, possibly the greatest cricket batsman ever to play the game, had reaction times on normal tests that were similar to a researcher’s control subjects who were college students.

For many readers, Ericsson’s work is a revelation, a way to—as Ericsson, Prietula and Cokely (2007) put it—‘demythologize’ the legend of the ‘natural’ expert or the gifted ‘prodigy.’ They point out that even Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart actually trained vigorously from the age of four, and benefited from having a father who was not only himself an accomplished composer and famous music teacher, but also author of one of the first books on violin instruction. A number of recent books, including Geoff Colvin’s (2008) Talent Is Overrated, and Daniel Coyle’s (2009) The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How, provide popular versions of Ericsson’s research, which has appeared in a number of forums. I’ve sampled some Coyle’s, and he highlights the environments that produce extraordinary hotbeds of ‘natural’ talent, such as the high intensity ‘salon soccer’ in Brazil that shapes players legendary ball handling skills.

Talent: A difference that makes a difference

Some frequent readers may think that, since I seem to often argue for the influence of ‘nurture’ or environmental effects on emerging traits, I would fall into line with Ericsson’s work, so powerful a case does he make for the production of expertise by systematic practice. What I will suggest instead is that, in a neuroanthropological model of talent, we must take account of how very early differences in ability or behaviour intersect with cultural conceptions of ‘talent’ to feed the dynamics that Ericsson describes. That is, as Ericsson is so clear, access to coaching and motivation are crucial to the emergence of expertise, and both of these resources are culturally shaped to intersect with early physiological and neural traits.

Cultural notions of ‘talent’ and very early differences in children both play a crucial part in the practical processes that produce expertise, even if only as a gateway variable preventing many from ever getting the resources necessary for deliberate practice.

In what is perhaps an overly glib description, I would say that from a neuroanthropological perspective, ‘talent’ is a difference that makes a difference. That is, my research on ‘talent’ across cultures—admittedly still very much in the developmental stage—suggests that different societies, diverse approaches to coaching or athletic environments, and various sporting regimes label different traits ‘talent’ or cause an athlete to stand out. That is, what one coach might call ‘talent’ another might not consider the clinching detail; a trait that might make an athlete stand out in one style of competition might not be salient in another.

For example, I remember very clearly being in grade school and playing a lot of soccer; at one point, ‘juggling’ a soccer ball became a measure of aptitude for playing in elite teams. That is, being able to stand in one place and keep the ball in the air by playing it off the feet, knees, chest, head and shoulder, emerged as the gold standard of ‘talent’ or excellence. Those soccer players who did not juggle as well as their peers were ‘less talented,’ even though they might be extraordinarily fleet of foot, have great endurance, have a vicious shot, or have excellent anticipatory ability for playing defence. Juggling was actually a separate skill, learned outside of playing, but it was taken as an index of ‘potential.’

This particular difference trumped other types of difference that might be seen as indicating future promise. In fact, the trait highlighted as a marker of ‘talent’ might be linked to future expert performance or skill, but not necessarily in a direct way. That is, unlike Ericsson’s model, I’m agnostic about ‘talent’ because I believe it is possible—possible—that very early differences in ability might be linked to later differences in experts’ abilities, but my observations lead me to be deeply dubious.

So how do we understand the links between early and later differences in abilities? Bear with me while I provide a diagram.

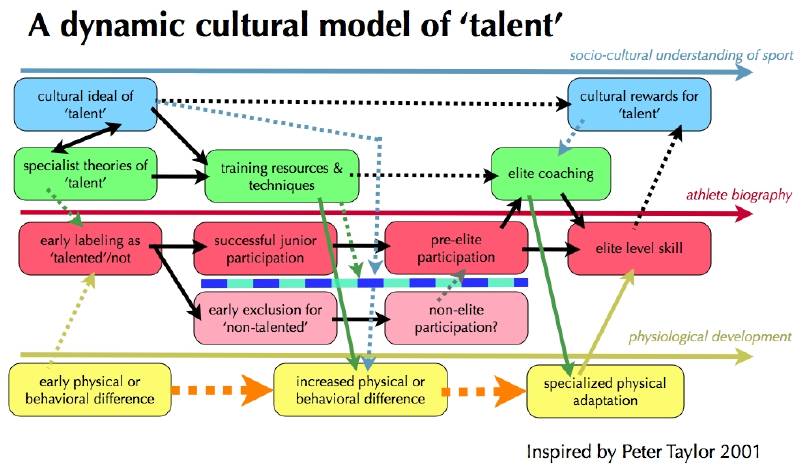

‘Talent’ as a cultural model

I first came up with a version of this diagram for a talk I gave at Macquarie University’s Centre for Cognitive Science, but I didn’t really get a chance to talk about it much (I’ve discussed some of that talk in my earlier post, Escaping Orientalism in cultural psychology). They’re based on work in dynamic systems modelling done by Peter Taylor (e.g., 2001), who influenced my thinking quite a bit when I spent a year at Brown University and encouraged me to experiment with using complex visual models to help me think about these sorts of systems (Peter’s versions make mine look kind of simple, albeit pleasantly colourful).

The three arrows across the whole diagram are intended to indicate a difference of scale; factors at the top are socio-cultural in scale, in the middle are psychological or individual, and at the bottom are neurological or physiological. Developmental time is meant to stretch from left to right so that the middle arrow is a kind of biographical trace.

The diagram is intended to suggest how cultural notions of talent, coupled with physiological, neurological and behavioural difference, lead some individuals to be labelled ‘talented.’ On the cultural side, there’s a complication which arises with specialized coaches or ‘talent scouts,’ who often possessing specialized knowledge or techniques, but are also influenced by predominant ideas of talent, just as they impose their own on young athletes.

One area I’m trying to study is how the front-line of contact with coaches, the individuals working with junior athletes, do or do not incorporate new research and ideas disseminated by sports governing bodies, researchers, professional coaches and the like. I suspect that there may be enormous inertia against, or even outright defiance of, sophisticated models of how expertise emerges coming from the actual coaches doing the athletic ‘triage’ in clubs, junior teams, and the like.

Once a young athlete is identified as ‘talented,’ he or she is then, to varying degrees, separated from ‘non-talented’ or ‘less talented’ peers and given access to resources that less promising young athletes will not receive. The initial difference, the symptom of ‘talent’ or ‘promise,’ leads through social and coaching mechanisms to a later difference, elite skill, whether or not the initial difference is organically or developmentally linked to the elite skill that eventually develops in any direct or causal way.

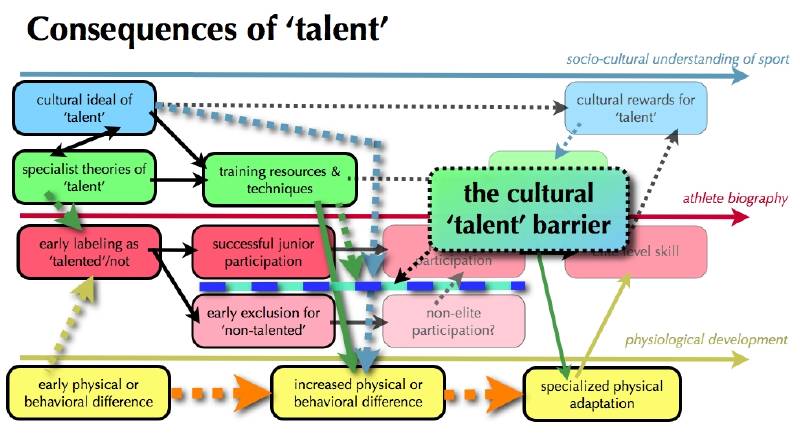

This divergence is represented by the two possible developmental trajectories in the middle register (in red and pink). The blue and green line separating them, I’ve called the ‘cultural “talent” barrier’ because of my natural knack for zippy names. This second version of the diagram focuses on some of the factors that make up, and arise because of, the cultural ‘talent’ barrier.

The cultural ‘talent’ barrier

The metaphorical ‘height’ of the talent barrier, that is, the difficulty that a child initially identified as ‘unpromising’ would have eventually gain enough skill or access to win re-evaluation, will depend both on the concept that coaches and society have of ‘talent’ as well as on the actual physiological consequences of the training regimen. That is, if enough resources are thrown at ‘talented’ kids, and those initially classified as ‘not talented’ are starved of opportunities for deliberate practice, expert coaching, or sufficiently de-motivated by the experience, the neurological and physiological consequences of cultural understandings of ‘talent’ will have very real consequences, making the initial assessment into reality.

The resulting experts will look different than more normal, under-achieving peers. For example, Dan Peterson discusses a recent article using brain scans of golfers in his piece, Tiger’s Brain Is Bigger Than Ours. The original article in PLoS ONE, The Architecture of the Golfer’s Brain, by Jäncke and colleagues (2009), makes two key points: first, that practice time directly correlated with golfers’ expertise (measured by their handicap) and that there was a stepwise quantitative difference in gray brain matter area in sensorimotor and cognitive areas linked to precision swinging (the left dorsal pre-motor and parts of the posterior parietal cortex in right handers). Jäncke et al. write,

the current finding supports the idea that neuroanatomical changes are induced by intensive golf practice…. These data are consistent with the view that the anatomical changes might have occurred at some point after the first 800–3000 practice hours or after a practice impact of more than 310 practice hours per year. In other words, anatomical changes may be induced by decreasing the golf handicap in early training phases to a handicap of approximately 15, whereas further practice, which is evidently necessary to achieve the proficiency of an elite golfer (associated with an average total of 27,000 practicing hours or 1,730 practise hours per year in this study), does not contribute any further to neuroanatomical reorganisation.

A cultural ‘talent’ barrier may be high in a particular sport, then, because of the peculiarities of the neuroanatomical adaptations that have to be made, or because of social and cultural factors that make it appear early promise is necessary to gain later expertise.

If the cultural barrier is low, we would expect that adults assume some kids don’t show promise until later, don’t give too much extra training or expertise to those youngsters with early advantages, and keep a broad segment of the population engaged, even if everyone involved isn’t convinced that they will be very good. Given this ‘low barrier’ condition, we would anticipate movement of individuals back and forth across the ‘talent’ barrier, less anxiety about being left off of a select team or failing at a try-out, and encouragement to keep trying as well as widespread opportunities to train systematically.

The promotion of ‘talent identification’ early in athletes’ development could theoretically lead the cultural ‘talent’ barrier to grow less permeable: those identified young would be given much greater opportunities for increasing expertise with very real physiological and neurological consequences. ‘Untalented’ individuals would also be clearly identified with corresponding impact on their development. The best coaching resources would be put at the disposal of a small group. If the young people believed their diagnoses, and then trained (or ceased to train) based on these assessments, the designation would profoundly affect the extraordinary motivation needed to undergo 10,000 hours of deliberate practice.

To put it simply, talent identification can become a self-fulfilling prophecy, pernicious because it widens the gap between those who are ‘promising’ from those who do not show early signs of ‘talent,’ even if those alleged markers of talent do not actually feed directly into the final expert result. That is, talent identification may focus on variables that are irrelevant for future accomplishment and yet still produce both enormous disparity and achievement in those labelled ‘talented,’ although the labelling is empirically incorrect (outside of the socio-cultural coaching system itself).

What may be a small initial difference, even a neurological advantage, can be compounded and exacerbated in many cases by the culturally-based perception that the small initial difference represents ‘talent,’ some innate superiority waiting to reach fruition. Once a person is identified as ‘talented,’ the socio-cultural mechanisms around sport that embrace and seek to develop that talent, to varying degrees fix that early diagnosis by transforming it into a distinctive developmental niche. In part, I take as evidence of this the well researched observation that children who are older for their age brackets are more likely to ‘excel’ at sports and be considered talented controlling for other factors; the slight differences—and sometimes not-so-slight differences—arising from less than 12 months increased physical maturity lead to a self-fulfilling bias in the older athletes’ favour (see the discussion of this research in A Star Is Made by Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt, with links to original papers at Freakonomics in the Times Magazine:

A Star Is Made).

Given Ericsson’s work on the effects of deliberate practice, including the neurological and physiological consequences, whichever trait is singled out as symptomatic of ‘promise’ will have an effect as a gatekeeper to resources or provocation for support mechanisms that encourage the development of skill. For example, if talent scouts looking at junior tennis players focused primarily on the velocity of a young player’s serve, those who matured fastest, becoming the biggest, would tend to be classified as ‘talented.’ Ironically, systematic study of junior tennis players who achieve success actually shows that they tend to be under-sized as junior players, catching up to their peers later, just the opposite of one potential way to identify ‘talent.’ Likewise, Helsen and colleagues (2000) suggest that much of what is identified as ‘talent’ in junior soccer may be physical precocity rather than a permanent advantage in dexterity, body control, or skill. Or from my earlier example, juggling ability in soccer may (or may not) be linked to later expertise; it may even be a secondary indicator, a symptom of a young athlete having the motivation or perceptual skills necessary to learn more important skills. Juggling would correlate well with success even though the skill itself might be irrelevant to later accomplishment (and the time spent on it, in some sense, wasted).

The initial advantage may be surmountable in neurological terms, but buttressed by cultural expectations. Draganski and colleagues (2004), for example, found neurological changes in adults who trained to juggle. As two of the authors later reviewed (Draganski and May 2008), these findings are part of an emerging recognition in brain sciences that plasticity exists in the adult brain, outside of what were once believed to be critical developmental windows. As a cultural belief, however, the idea that the adult brain cannot change was (and is) part of a ‘talent’ barrier, discouraging late-developers from believing that they have a chance to develop skill.

Dan Peterson in Science Daily discusses How to Pick Athletic Superstars at Age 1, and comes to similar conclusions: although genetic tests for ACTN3 variations met with initial excitement, as variants of the gene have sometimes been linked to the prevalence of fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibres, follow-up research has made the excitement about ACTN3 seem a bit premature. Predicting future athletic greatness on the basis of a genetic marker, or even on the basis of early achievement, runs contrary to basic research about how expertise emerges, including the extraordinary motivation, support, and commitment that development takes.

Through circuitous mechanisms of ‘talent,’ however, differences among novices can lead to elite abilities, but not because those elite abilities are already present, inchoate in the novice. Paradoxically, for some athletes, early rejection or frustration can help provide the stimulus for determined training and self-development. By the time the developmental trajectory reaches elite levels of refinement, extracting the effects of training, social selection, positive (and negative) reinforcement through affirmation (or discouragement), and self-fulfilling prophecy, is impossible.

The future research

The research project that I am working on right now, the one I’m writing grant applications for and doing all that sort of time-consuming, hair-pulling sort of work, includes work on cultural differences in the identification and development of ‘talent.’ That is, I suspect the traits that get a young person identified as ‘talented’ vary across cultural contexts.

Here’s a case where the initial variable that may make a child appear ‘talented’ or ‘not talented’—precocity of child development and onset of growth spurt—may or may not be linked to a later relevant physical advantage in the sport. Not only is bigger not necessarily better in rugby, but a lot of late developers catch up to and bypass their bigger peers. Polynesians make up something like 40% of all professional rugby league athletes in Australia, but they occupy a range of positions, demonstrating that their size is not necessarily always the key foundation for their elite-level skills. Moreover, if the nervous system is faster developing in boys with early growth, the extreme plasticity of adolescence, when so much coaching work can be done on skill development, might end more quickly (this is purely a hypothesis). But if small boys are chased out of the sport for fear of injury, the cultural barrier to developing their skill is quite great, but one that could be surmounted by a number of simple mechanisms (such as weight-graded teams or lower contact variants of the sport to encourage skill development).

In another rugby-related example, some sporting systems are quite selective at an early age. I’ve watched my nephew move through multiple layers of ‘select’ or ‘representative’ squads, being chosen to play for his quarter of the city, for Sydney ‘city’ against New South Wales ‘country,’ for our state against other states, and then for Australia, all before the age of sixteen. For a person making it through this extraordinary system, the affirmation is enormous and the accumulation of access to coaching resources at each stage of this process helps to crystallize and widen any initial advantage the successful young athlete might have possessed. In contrast, the vast majority of rugby-playing hopefuls have had to face rejection at some stage of this process, told to ‘keep trying for next year,’ but given the implicit message that they are inadequate already at an age when most of them are far from physically mature.

Other sporting systems may not be nearly as selective. I marvel at extraordinary participation levels for men in rugby in New Zealand; even at the relatively senior age of 35+, participation in full-contact rugby is 11% (see SPARC 2001). Even more strikingly ‘democratic’ than the New Zealand case are some of the figures I have heard for participation in Australian-rules football in the Tiwi Islands, where it is rumoured that 40% of the whole population is involved in playing.

Although I have yet to really do the ethnographic fieldwork I need to put this in perspective, I have a strong sense that the ‘club’ approach to rugby in New Zealand contrasts with the severely age-graded selective environment I saw in Sydney, or in many sports in the United States. In the US the collegiate sporting system simultaneously encourages elite athletes to concentrate even harder (with scholarships at stake) while it demotivates many people from continuing to participate (for example, among those who do not go to university).

I suspect that ideas about ‘talent’ and socio-cultural arrangements of childhood sport affect each other. The rise of select teams or the contrary development of more widespread participation in sports can both help convince people that talent is either rare or widespread, with real physiological consequences for how the initial differences among children either become exaggerated or mitigated by training techniques.

Although this is only one dimension of the project, I think it’s one that has clear applications in youth sport and other social mechanisms that produce expertise over time. Clearly, there are initial differences in ability, some of which may be due to innate advantages in some individuals. But I suspect that a cultural system designed to identify ‘talent’ early and concentrate coaching resources on those with early promise can actually make the expert skill more rare as it demotivates those who might develop expert skill without the early advantage or mature more slowly. Rigorous talent identification may produce a handful of highly skilled individuals, but it may concentrate training resources so much that it makes the overall skill more rare than in a more open developmental program.

Conclusion

In summary, although I agree with Ericsson that expert performance clearly requires extraordinary efforts at development, strong coaching, and intense motivation, I don’t want to underestimate the importance in this process of very early differences in ability. Far from being irrelevant, early differences may contribute to future expertise, as they are compounded, exaggerated, or even leveraged into entirely unrelated abilities. If resources are allocated depending upon early diagnosis of ‘talent,’ then talent matters. The more a society believes in ‘talent,’ the more likely it is to become a reality, and the greater disparity we are likely to find between those designated as promising from those who don’t show early promise.

Given this approach to ‘talent,’ I don’t think it can be divided into a portion that is ‘innate’ and another that is ‘learned’ or ‘developed.’ Talent is a difference that makes a difference, either because it lays the foundation for future skill or because it unlocks access to socio-cultural structures that help a person to generate greater skill, but more likely because it does both. It’s not easy to separate those differences that are ‘foundations’ from those that are more social ‘keys.’

Part of the problem with the idea of ‘talent’ is that it discourages researchers from looking more closely at which developmental factors might produce the initial difference that gets compounded or what makes some people respond to one type of training when others do not. ‘Talent’ becomes a garbage variable, a way of explaining the unknown without really studying it more closely. ‘Talent’ locates all the cause for differential outcome in the individual, making it very hard to conceive of any other way to increase expertise than to look harder for ‘talent’ and spend more on developing it when it’s identified. In some cases, ‘talent’ may be a match between a distinctive pattern of motor control or style of perceptual processing with the task at an early stage or the selection structure, one that, if we understood it better, we could compensate for in others or even coach its development better.

Although it might be possible to develop more precise tools for identifying talent, discarding cultural concepts that are misleading or just wrong about which sorts of early developmental difference are actually predictors of future success, I don’t think that this is the best strategy. Ericsson’s research suggests very strongly that what is really in short supply in the cultivation of expert performance is not initial ability, but rather expert coaching and motivation to continually develop greater skill. In some ways, the popular versions of Ericsson’s work may help to fire more motivation; I’m hoping that some of the other dimensions of my research might help address the shortage of expert coaching, but I’ll save that discussion to another post.

Credits:

Thanks to Dan Peterson at Science Daily and Sports Are 80 Percent Mental for continually providing excellent discussions of the implications of sports science research. Thanks also to John Sutton and the folks at the Macquarie Centre for Cognitive Science, for their feedback and thoughts on the project.

If you’re interested in the work of K. Anders Ericsson, definitely check out his website and publications, or consider reading one of the popular books based on his work.

For more on the controversy about large boys in junior rugby, see Is Fotu, 9 and 85kg, too big for his teammates’ boots? at ourfootyteam.com

Please cite this materially responsibly as this is, like everything on Neuroanthropology.net, an intellectual labour of love for the authors.

Stumble It!

Stumble It!

References

Abernethy, B. 1987. Selective attention in fast ball sports. II. Expert-novice differences. Australian Journal of Science and Medicine in Sports 19(4): 7–16. (abstract)

Colvin, Geoff. 2008. Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World Class Performers from Everybody Else. Portfolio.

Coyle, Daniel. 2009. The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How. Random House.

Draganski, B., C. Gaser, V. Busch, G. Schuierer, U. Bogdahn, and A. May. 2004. Neuroplasticity: Changes in grey matter induced by training. Nature 427(6972): 311–312. doi:10.1038/427311a

Draganski, B., and A. May. 2008. Training-induced structural changes in the adult human brain. Behavioural Brain Research 192:137-142.

Entine, Jon. 2001. Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It. New York: Public Affairs.

Ericsson K. Anders, Ralf Th. Krampe, and Clemens Tesch-Römer. 1993. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review 100(3): 363–406. (pdf available here)

Ericsson, K. A., and A. C. Lehmann. 1996. Expert and Exceptional Performance: Evidence of Maximal Adaptation to Task Constraints. Annual Review of Psychology 47: 273-305. (pdf available here)

Ericsson, K. Anders, Michael J. Prietula, and Edward T. Cokely. 2007. The Making of an Expert. Harvard Business Review 85:114-121. doi 10.1225/R0707J online version available here.

Helsen, W. F., N. J. Hodges, J. Van Winckel and J. L. Starke. 2000. The roles of talent, physical precocity and practice in the development of soccer expertise. Journal of Sports Sciences 18: 727-736.

Houghton, Philip. 1990. The adaptive significance of Polynesian body form. Annals of Human Biology 17(1): 19-32. (abstract)

Jäncke, Lutz, Susan Koeneke, Ariana Hoppe, Christina Rominger, and Jürgen Hänggi. 2009. The Architecture of the Golfer’s Brain. PLoS ONE 4(3): e4785. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004785

Regnier G, Salmela J, and Russell SJ. 1994. Talent detection and development in sports. In Singer R. N., Murphey M., Tennant L. K., eds. Handbook of Research on Sport Psychology. Pp. 290–313. London/New York: Macmillan.

SPARC (Sport & Recreation New Zealand/IHI Aotearoa). 2001. SPARC Facts: Rugby Union. Information from Sport & Recreation New Zealand’s (SPARC) 1997/98, 1998/99 & 2000/01 Sport & Physical Activity Surveys. Available at: www.sparc.org.nz/research-policy/participation-in-sport

Starkes JL, Deakin J. 1984. Perception in sport: a cognitive approach to skilled performance. In Cognitive Sport Psychology, ed. WF Straub, JM Williams, pp. 115–28. Lansing, NY: Sport Sci. Assoc.

Taylor, Peter. 2001. Distributed Agency within Intersecting Ecological, Social, and Scientific Processes. In Cycles of Contingency: Developmental Systems and Evolution. Susan Oyama, Paul E. Griffiths, and Russell D. Gray, eds. Pp. 315-332. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Immensly interesting and well informed. Thank you for sharing. : )

in the discussion about talent being to a large extent a matter of deliberate practice, I wonder if this assertion has not a threshold at the upper end, i.e.: can this assertion also be maintained for exceptional talents in science such as Mozart, Leonardo da Vinci, Glenn Gould?

I would appreciate your view.

With kind regards

H. Kreuzer

Please feel free to have a look at this article here: ‘What is Talent?’

http://www.talent-technologies.com/new/2011/08/what-is-talent/

Certainly as the brain develops, there is a clear development of ‘talents’ and these have been mapped in a scientific, objective way.

Being a sportsman myself I have little doubt that the nature of these talents translate into performance differences in numerous different fields of sport.

Yes, Joe Talent, it is possible to believe one’s cultural categories quite successfully. Even run a business based on them. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that these particular categories are the best way to understand a scientific issue. Selling people on the concept of talent is easy — most Westerners believe it already — but that doesn’t mean it’s accurate. You might consider reading research on elite skill acquisition. If you do, you’ll find that this research is often MORE critical of the idea of talent than I am. I actually think that there are pre-existing differences in ability that get sorted by the social apparatus that believes in ‘talent.’

does a person has more than one or two talent

This is what I believe. People say that I am talented in art. What this really means is that I have been deliberately practicing at least since I was 5 years old. People who say, “I wish I could draw like you do,” don’t mean it literally. If they did, they would start practicing. People who say, “I can only draw stick figures!” are making an excuse to avoid trying to draw better than stick figures, so they’ll never draw better. Why don’t people say, “I can’t drive, I can only ride a bicycle”?